120 Australians hospitalized every week due to domestic and family violence

“I believe that workplaces can play a large role in supporting individuals who are suffering as it can create a safe space, both physical and mental, that’s sometimes disconnected to a victim’s personal life.”

So says Rob Stone, chief people officer at CHEP Network, in talking to HRD about the pressing issue of domestic violence.

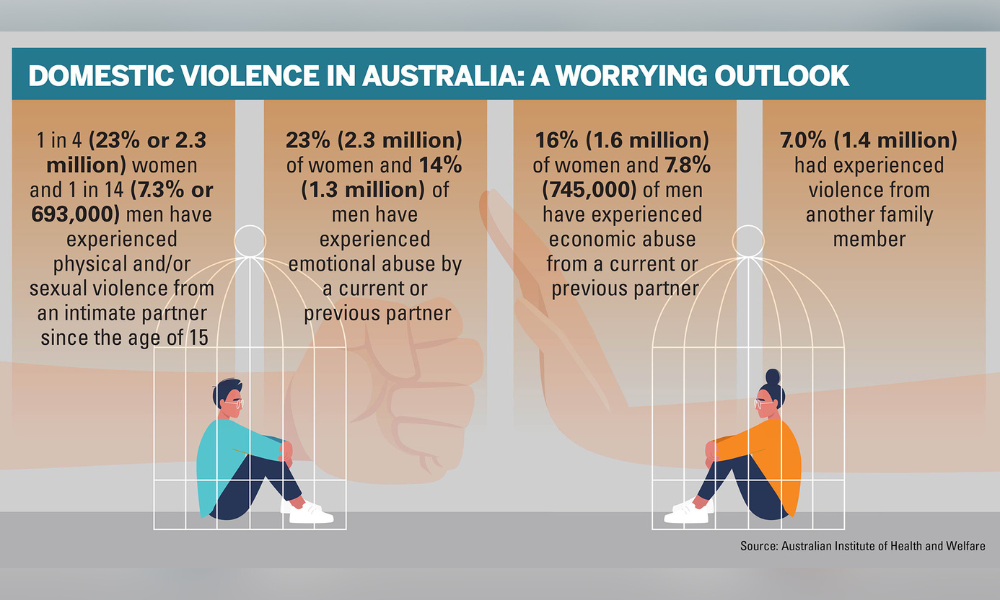

One in four women in Australia have experienced domestic violence, with 23% reporting that at least one incident of violence came from a partner or ex-partner. What’s more, a staggering 120 people are hospitalized every single week due to domestic and family violence, according to the government.

And while new government measures around domestic violence leave have set a good example, a shockingly low number of people are actually using it.

Why? Stone says it’s a combination of fear of retaliation and a lingering, unwarranted stigma.

“I believe that we’ve come a long way when it comes to serious issues such as mental health in the workplace as we needed to,” he says.

“However, we still have a long way to go in areas such as domestic violence. There’s a real issue in general - not just the workplace - regarding the reporting of domestic abuse. Most victims won’t report due to fear or revenge or further violence, embarrassment or shame or that victims feel that it’s insignificant.

For many employees, it’s this fear of retaliation coupled with a lack of understanding around the leave that’s preventing them from reaching out to their employers.

“Domestic violence is so complex and damaging and goes beyond just physical violence,” adds Troy Plummer, AU head of legal at Irwell Law.

“It can be emotional, psychological, financial or sexual, to name a few examples. Having a leave entitlement for family and domestic violence situation is a significant and much-needed step forward, but it’s clear by the lack of uptake that more needs to be done.”

Needless to say, family and domestic violence is an incredibly sensitive topic, Plummer says.

“Victims grapple with feelings of shame, guilt and isolation, making it difficult for them to disclose their experiences to anyone, let alone their employers. Feelings of weakness and shame, as well as fear of judgement or even job loss, are key reasons that deter people from taking this type of leave.”

Despite the fact that the Fair Work Act demands confidentiality in the reporting of domestic violence to an employer, that isn’t always enough reassurance for a victim, Plummer says. Couple this with the sheer lack of awareness around leave entitlement and eligibility, it’s little wonder the uptake continues to remain low.

“While family and domestic violence leave is a necessary provision in the Fair Work Act, employers must go beyond simply having words on paper to improve its uptake in Australia,” adds Plummer.

“To effectively address this issue, they must create a supportive and inclusive workplace environment. This includes implementing clear and accessible policies, providing comprehensive training for staff on domestic violence, and fostering a culture of confidentiality and empathy. Collaborating with external support services like 1800RESPECT can also equip employers with the resources to offer necessary support to affected employees.”

According to the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations, leave entitlement provides an employee with access to 10 days’ paid family and domestic violence leave over a 12-month period – this includes full-time, part-time and casual employees.

To access the leave, employees should explain the situation to their employer as soon as possible. The employer may then ask for evidence to support the request – this could come in the form of:

“In the same way that employers cannot refuse a legitimate application for sick leave, they also cannot deny a legitimate request for family and domestic violence leave,” adds Plummer. “Employers can’t request extensive evidence, but they can ask for a basic explanation. In the same vein, employees have a right to privacy and don’t need to divulge the details surrounding the need to take the leave.”

While employers are within their rights to request proof of the application’s legitimacy, Plummer strongly advises them to approach any discussions with the employee about the request “with compassion, respect and empathy,” he says.

“It’s an incredibly sensitive and personal subject, and the last thing you want to do is discourage your employees from coming forward and seeking help.”

Furthermore, it’s important to remind both employers and employees that the Fair Work Act requires that any evidence provided to support a leave application must be treated confidentially by the employer and may only be used to assess the requested leave.

For employers, there’s not only a legal obligation to help here but also a moral one. As Stone tells HRD, it’s the little things that can make all the difference to struggling employees.

“It’s not just about giving victims additional time off, it’s about giving additional support to people that are at their most vulnerable state. Do you help with providing accommodation, do you help with legal representation? Do you provide professional counselling services that are above and beyond your EAP providers? We also have unique job numbers for people that are needing to take time, to ensure confidentiality isn’t broken.

“Every person that is experiencing domestic abuse could require very different needs and support, so don’t have a rigid policy in place that, that makes it difficult for people to come forward.”

While there are no specific appeal rights under the Fair Work Act to challenge a refusal of family and domestic violence leave, there are three primary avenues open to employees in case of a request refusal.

The first would be raising a complaint with the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) who is charged with educating employers and employees about rights and obligations at work, explains Plummer.

“The FWO also enforces non-compliance with the Fair Work Act and the NES. This is likely to be the quickest avenue, as the FWO has inspectors and other officers who could readily approach an employer and advise them of their obligations.”

The second could be an employee approaching their union if they are a member, or a lawyer, to get their assistance in advising their employer of their rights.

“Finally, lodging a general protections claim in the Fair Work Commission alleging adverse action has been taken against them in respect to their being denied the requested leave,” adds Plummer.

“This is probably the most time-consuming and potentially costly option. Although most processes in the FWC are fairly efficient, such a claim would still take weeks or possibly a few months to move through.”

Unfortunately, if it could not be resolved by agreement in the FWC, then it would have to go to the Federal Circuit Court or Federal Court, Plummer says, “which is a poor option for such a fast moving and imperative issue as taking this leave is in response to threatened or actual violence.”

Engaging in these conversations is much easier when you have an overall inclusive and safe culture, adds Stone.

“I believe that all of us as humans have a duty of care to look out for each other. Ultimately, it’s on the individual to come forward in these situations; however, as mentioned earlier, make these conversations as easy as possible by normalizing open and progressive policies and procedures.”

Lastly, it’s important to also ensure that people that are helping or providing support don’t get involved or also become a victim.

“It’s important that anyone who engages or becomes involved is mindful around how they communicate. You never know what people are capable of and if you ever feel unsafe or at risk, inform the police straight away.”