Amendments to the Fair Work Act will change how employers confront abuse

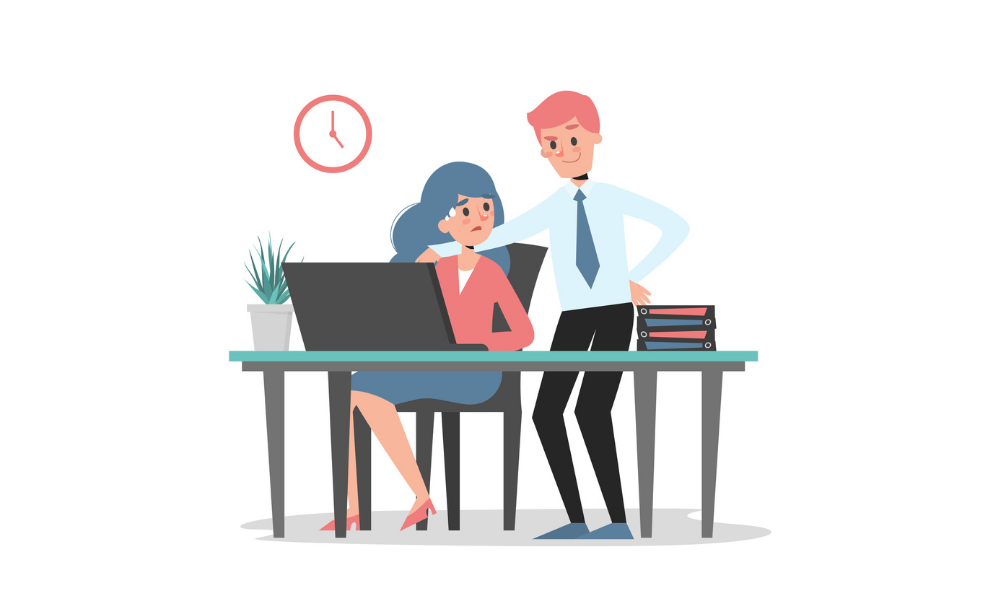

With a return to the office imminent across most states in Australia, workplace laws that haven’t had to be tested with stay at home employees, will be back in force. The shift to remote work meant that HR leaders had to adapt to what ‘harassment’ looked like in a digital world – now, as we head back into the workplace it’s time to turn our attention back to preventing in-person abuse.

“Firstly, companies must ensure that they have written policies in relation to bullying, sexual harassment, harassment and discrimination, as well as clear procedures in place for raising grievances,” Sally Woodward, Partner, industrial relations and employment law at PwC Australia, told HRD. “Those policies must be fit for purpose. For example, the way in which complaints about sexual harassment are managed has changed exponentially over the last few years, and procedures should be adapted to reflect that and to ensure a more ‘victim centric’ approach.

“It isn’t enough just to have policies in place, a company needs to create a culture where inappropriate workplace behaviour is not tolerated. Workers need to be empowered to speak up if they are subjected to or witness inappropriate behaviour. Leaders need to ensure that workers have sufficient trust in the system to know that they can do so without fear of reprisal and that speaking up will lead to action being taken.”

In June 2018 the Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Kate Jenkins, and the then Minister for Women, Kelly O’Dwyer, announced the National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces. The Respect@Work Report was published following the inquiry, which sets out 55 recommendations for addressing sexual harassment in workplaces, including a range of potential legislative reforms. The Australian Government responded to the Report with its Roadmap and amendments to the Fair Work Act (Cth) and the Sex Discrimination Act (Cth) (SDA) have been made to implement some of the recommendations that were made in the Report.

The amendments to the Fair Work Act included the right for employees to bring a claim to the Fair Work Commission seeking orders that sexual harassment in the workplace stop, which is very similar to the stop bullying jurisdiction in the Fair Work Commission. The amendments to the SDA have the effect of introducing a stand-alone offence of sex-based harassment, as well as numerous other changes which clarify/remove ambiguities, and modernise the legislation to expand coverage to protect all workers from sexual and sex-based harassment in a modern work context.

“Whilst there is currently no positive obligation to eliminate sexual harassment within a workplace, a company has general WHS obligations that impose a positive obligation to ensure the safety of its workers so far as reasonably practicable,” Woodward said. “Sexual harassment is obviously a risk to both physical and psychological safety and therefore a company must take steps, so far as is reasonably practicable, to ensure that workers are not exposed to sexual harassment whilst at work. That includes whilst working from home.

“Harassment and bullying can - and does - occur via online, virtual or electronic communications and an employer needs to ensure that all workers understand that its policies and processes in relation to bullying and harassment apply to remote working and online communications. Employers need to reinforce the importance of respectful communications at all times.”

Companies are obliged to raise concerns over workers on issues such as harassment and bullying in a timely fashion to ensure expediency and efficiency in dealing with the matters. All issues raised must be taken seriously and properly investigated.

“Employers should conduct a risk assessment to see if there are areas of particular risk within the workplace that might lead to inappropriate behaviours, for example because of a known lack of inclusivity, or a clear power imbalance, or because the industry is particularly high risk,” Woodward said. “Employers should take steps to ensure that it concentrates its efforts to build an understanding of the expected standards of behaviour in those higher risk areas.

“Leaders within the organisation must lead by example, modelling the right behaviours, and there must be clear consequences for those who do not. Transparency is also important to help employees understand that there are consequences for breaching the applicable policies.”