Rather than persisting with inflexible formulas, high performing companies are taking a more holistic approach to short-term incentives. Stephen Burke outlines how to achieve the best outcomes from your strategy

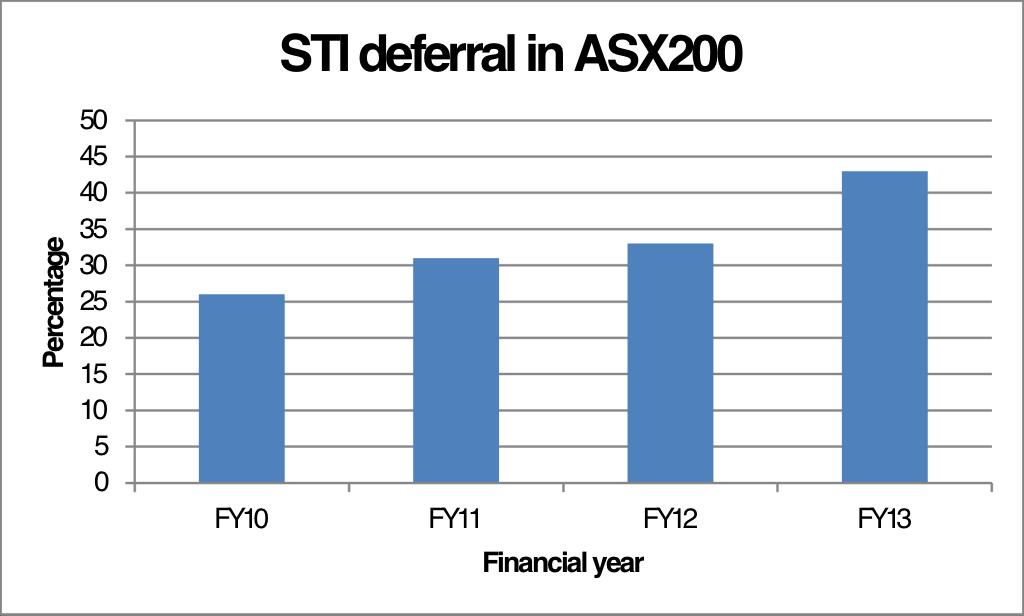

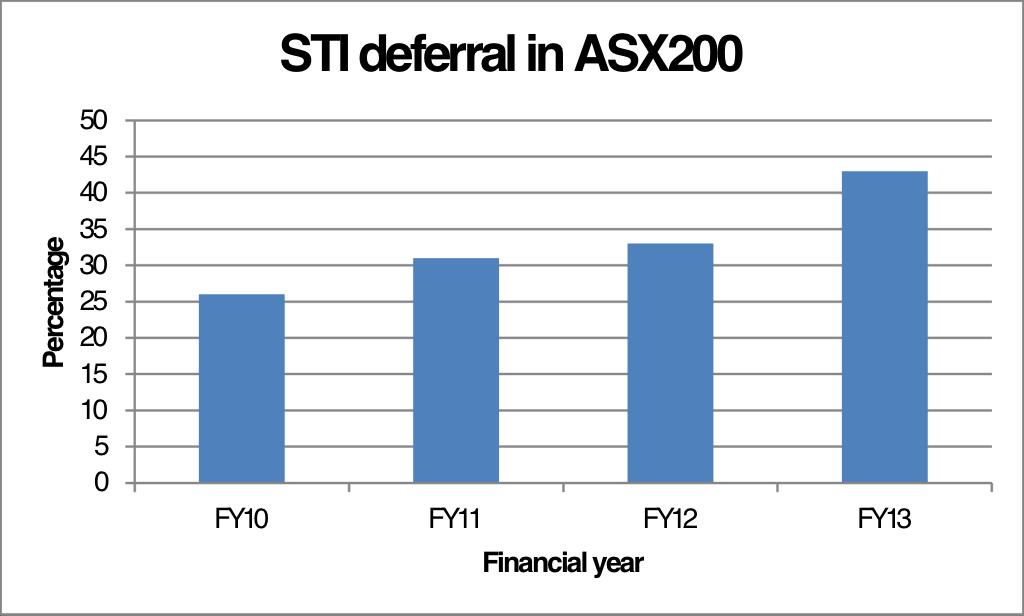

After the GFC, shareholders, proxy advisers and the government called for closer alignment between pay and performance – with a special emphasis on reducing the risk in incentive practices to ensure they rewarded sustainable financial performance. This has resulted in a number of trends for short term incentives (STIs).

We’re seeing increases in STI deferral, typically for one to two years, and a further emphasis on quantitative STI formulas, often tied to profitability (providing a clear link to financial performance for shareholders and executives). At the same time, there are decreases in discretionary overlay and volume-based performance metrics (such as revenue), primarily in financial services, where regulation has sought to prevent manipulation and shift attention to profit margins.

Many organisations believe they are taking a more holistic approach to performance management by using balanced scorecards. The objective is to align an individual’s pay with all aspects of their role – particularly those areas they can directly impact. Last year, Australian companies attached more metrics to STIs than others in the Asia-Pacific region. About a third of Australian companies use eight or more metrics, while another third use between five and seven. The remaining third use four or fewer (2012 Asian Incentive Plan Design Survey, Towers Watson). Across the region, organisations typically use three metrics.

WEAKNESSES OF THE CURRENT APPROACH

The most common fault of STIs is they don’t align with business strategy. Organisations often revise remuneration programs incrementally to address specific issues, rather than take a step back to consider how STIs (and other incentives) fit with overall remuneration and business strategies.

Another weakness is that formulas applied to STIs can be inflexible and unpredictable. Yet searching for the perfect formula that simply and accurately reflects organisational, business unit and individual performance and allows for the effects of unexpected events is futile. STI formulas continue to result in unintended consequences because they can’t capture all the circumstances relevant to a complex business. Formulas are often introduced to provide certainty of outcome to the board, participants and shareholders but can become a straight jacket when unusual circumstances arise. When formulas backfire, boards must choose between:

- Sticking with the formula and, as a result, disappointing shareholders, who may have suffered a significant fall in value, or participants, who may have created or saved significant shareholder value by responding effectively to an external shock beyond their control, but whose earnings are significantly reduced because the formula emphasises only one aspect of performance (often financial).

- Using discretion to adjust or abandon the formula to recognise all circumstances. But this ad hoc approach undermines the rationale behind the formula (which is to provide certainty) and damages the credibility of the plan.

- A formal option for boards to apply discretion on STI payouts, which is important if directors are to effectively discharge their obligations to all stakeholders, but needs to be an acknowledged part of the STI process and within a well-considered framework.

Our experience is that ad hoc bonus adjustments rarely reduce bonuses resulting from a windfall – after all, shareholders are happy too. We tend to see discretion more commonly exercised in favour of executives where “circumstances beyond their control” cause a loss of incentive. However, each use of discretion can be equally damaging where it occurs outside a proper framework. To the outsider it can appear that management always wins, and to the insider it can create a culture of special pleading that is equally damaging to a performance culture.

Yet another weakness of STIs are scorecards with multiple measures that disperse executive focus. Balanced scorecards require executives to focus on several KPIs – we regularly see examples of 12 or more – some of which have relatively small dollar values attached due to weighting towards financial measures.

Click image to enlarge

Organisations would do well to question whether each KPI is truly indicative of performance, or whether some are simply included to emphasise the importance of certain job responsibilities. Does a weighting of 2–3% of total fixed remuneration communicate importance to an executive? And does it focus them on critical activities that enhance shareholder value?

Balanced scorecards can also have an averaging effect on STI outcomes. For example, where an executive achieves a majority of non-financial targets, they may receive a substantial proportion of STI payment even when poor financial performance has occurred. This is the intention of the balanced scorecard (that financial performance not be the sole focus), but can be a difficult message to send to shareholders.

HIGH PERFORMERS ARE LEADING THE WAY

High-performing companies are taking a more holistic approach to executive STIs. Business strategy and company culture dictate the basis for STI design, incorporating a limited number of quantitative and qualitative performance measures. As a result, executives in high-performing organisations focus on how performance is delivered (is it sustainable/meaningful?) as well as the level.

The effect of organisational strategy and culture on effective STI design is shown in the table above, drawing on data from the Towers Watson Cultural Alignment benchmark.

For example, if a company’s strategy is predominantly driven by efficiency, its pay/performance management systems will be very different to one with a quality-focused strategy. It’s a useful tool when considering how to design a remuneration strategy and components to support the corporate strategy.

HOW TO ACHIEVE BEST-PRACTICE STI

The business environment changes continuously. High-performing companies manage this complexity and unpredictability by building a certain level of flexibility into incentive programs and clearly communicating the objectives and ground rules to stakeholders.

In designing STIs, high-performing companies ask:

- Are we paying for the right things – that is, are we measuring meaningful performance or execution of basic job responsibilities?

- Do we view performance holistically? Are we considering how performance is achieved alongside how much is achieved?

- How do we deal with unexpected events? Does the board have formal discretion and do stakeholders understand how it will work?

- Is our pay (including STI) consistent with our company culture and strategy?

Designing effective executive incentives is complex. There are competing and inconsistent priorities. Shareholders demand alignment, typically with their financial returns, and executives want to know what is expected of them in any given year, and what they will receive if they deliver. Everyone recognises that financial performance cannot suffice as a sole performance measure. However, managing conflicting viewpoints is a challenge for boards. While there is no single best practice incentive, a company must understand its strategy and desired culture, and have a clear plan to get there. Only then can an incentive be designed to support those objectives.

Click image to enlarge

Stephen Burke is director, executive compensation, Towers Watson

Stephen Burke is director, executive compensation, Towers Watson

Stephen Burke is director, executive compensation, Towers Watson

Stephen Burke is director, executive compensation, Towers Watson