There will always be a need for postgraduate business qualifications, but in a crowded market, where does the MBA fit in?

There will always be a need for postgraduate business qualifications, but in a crowded market, where does the MBA fit in?

The MBA was first offered by the Harvard University Graduate School of Administration in 1908; since then, MBA programs have been advancing the frontiers of skill and character development in their students. With an eye on technological, industrial, societal and ethical changes, the modern-day MBA is aligned with skills that enable graduates to produce tangible industry outcomes; indeed, it is MBA graduates who are our future leaders. However, the MBA is not without modernday challenges. The postgraduate business degree market has never been more crowded. MBAs must not only compete in a crowded market full of other MBAs but also with specialist master’s degrees, which have gained traction in recent years.

Does the MBA still hold its place in 2018? The consensus is a resounding yes – with some provisos.

It does not matter how fast businesses change, key skill sets for MBA graduates remain constant and relevant. These skills include complex problem-solving; critical and analytical thinking; creativity; managing, leading and coordinating people; emotional intelligence; judgment and decision-making; and cognitive flexibility.

“Traditionally, a great MBA program encourages its graduates to become self-aware and to have a keen awareness of the business environment and wider society,” says Ezaz Ahmed, MBA director, Flinders Business. “In addition to this, the MBA plays the role of educating students to become skilled data crunchers, analysts and great business leaders.”

The University of Sydney Business School launched an eye-catching PR campaign in 2017 along the theme of ‘the traditional MBA is dead’. Guy Ford, director of the university’s MBA program, says the MBA came of age in the 1950s during a period when the belief was that business operations needed to become more technical.

“You did your business degree, you went to a tech college and did bookkeeping. It wasn’t treated all that seriously in terms of formal study. People did arts and sciences and so on,” says Ford. “The early MBA was put together to bridge that gap, and they tended to take a modularised approach with a dose of accounting, economics, some HR and business strategy, put together almost like a buffet.”

While that approach served the world well for the next 50 years, when the University of Sydney Business School was looking to reinvigorate its existing MBA program, research revealed there was an increasing belief that, once an MBA was completed, “it doesn’t really matter where you’ve done it, it’s pretty much going to be OK with those business basics, reading a financial report, and so on,” Ford says.

In addition, there were skills gaps for graduates, which were becoming more apparent as businesses changed. “A lot of MBA grads have knowledge but not necessarily really good skills – interpersonal skills, critical analysis skills, problem-solving skills,” says Ford. “They can solve problems, but they tend not to ask if they are solving the right problems, and don’t look much deeper into the nature of the issues. Some of these skills are micro skills – how to have a confrontation effectively, active listening skills, team-building skills.”

Typically, Ford adds, these skills are difficult to teach; they require mentoring and coaching support, as well as experiential learning opportunities. “You can teach someone how to have a confrontation, but until you actually have people doing it over and over and getting feedback straight away, it won’t be cemented in the mind of the learner,” he says.

In addition, class sizes need to be smaller. “You can’t do experiential learning in a big lecture theatre that holds 500 people. You want that feedback from your peers and lecturer.”

A further piece of feedback received by the University of Sydney Business School was that fresh MBA grads were not being equipped to deal with ambiguity. “The way you deal with building resilience and helping people to cope with ambiguity is by ensuring you have a highly diverse cohort of students who come at problems from different perspectives and mindsets,” Ford says. “That’s diversity in terms of professions, qualifications, gender, background, and also other skill sets – so you have people who are out-of-the-box thinkers, people who are good integrators, or good at implementation, just like you’d expect in the workforce.”

The University of Sydney Business School’s revamped part-time MBA program, launched in 2013, has 50 students per intake, who are carefully selected to ensure diversity. A fulltime program kicks off in August this year. Although the MBA foundations are similar to what they’ve always been, the content and delivery have changed.

“We need to give students skills, give them a growth mindset and the confidence to operate lean and also to experiment. We also want to learn from each other,” Ford says.

“It’s less lecturing – in fact in some of the courses it’s virtually no lecturing; it’s more facilitating discussion. It’s the job of our facilitators to create these learning experiences and simulations.”

70:20:10 – with a focus on the 70:20

Echoing Ford’s sentiments about the need to upgrade the MBA is Tim Kastelle, MBA director at University of Queensland Business School. However, he also suggests students should be mindful of what an MBA can successfully deliver.

“You can do an MBA and say, ‘I want to learn really specific skills, like how to read a spreadsheet’,” he says. “However, those skills change very rapidly in response to technology. So if you’re saying, can we give people the skills they’ll need five years from now – the very specific mechanical skills – the answer is no, because it’s a moving target and it’s moving faster and faster.”

On the other hand, he adds, it is possible to teach people how to adapt to change and think about business problems through an innovation lens, and how to become more comfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty. “Those are skills that we absolutely need both in general and particularly to deal with change in the nature of work today,” Kastelle says. “A well-designed MBA program addresses those, but the tricky thing is they are harder to teach and assess. Therefore some MBA providers will drop back and teach the easier stuff, which is precisely the wrong thing to do because those are the things that are likely to become extinct sometime in the near future.”

When students undertake study at the level of an MBA, he says, “you’re dealing with people with management and work experience”. Their issue is not that they have a knowledge or information gap. They also understand best practice. For Kastelle, the critical question to ask is whether the program will help the student undertake business in a different way. Will it shake up established behaviours?

“That depends very much not just on what happens in the classroom, although it does happen when you have high levels of interaction or spontaneous discussions and exercises with people in the room, but most of that comes from the way the material is assessed, the activities you ask people to do, the tasks you ask them to engage in,” Kastelle says.

While UQ does informally use the 70:20:10 learning model, which suggests 70% of learning comes from challenging assignments, 20% from developmental relationships and 10% from coursework and training, Kastelle says it’s tempting to only concentrate on the 10% – yet it’s the 70% and 20% where changes in behaviour occur. “It’s those experiences outside the classroom that really cement the learning,” he says.

“Every time I run a class, at the end of it I ask people what they’ll do differently when they’re back in the office on Monday. If we don’t have an answer to that, we’ve wasted our time. That’s the 70:20 bit – how do we change actions? And that’s what we have to get to.”

Kastelle says the ‘doing’ is the hardest part of undertaking an MBA. He likens it to losing weight: it’s simple, but it’s not easy. “We know to lose weight you have to eat less and exercise more. It’s the simplest thing in the world, and yet there’s still this enormous market for personal trainers, diet books and plans, and soon – because actually doing it is hard. Good management is pretty much the same. There are fundamental things that don’t change in management in response to changes in technology and what’s happening at work; they are simple but hard to execute.”

Tech’s impact on MBAs

Helping with the execution is technology. Use of technology has helped MBA programs connect students to content.

“It is evident that technology has worked as a bridge between instructors and students and assisted students to learn better through increasing their engagement in educational activities,” Ahmed says. “Because of the development of educational technology, MBA programs are now successfully offered through online, blended, intensive, and of course in the brick-and-mortar format of face-to-face delivery.”

Technological advancement and the expansion of information and communications technology have also enabled accredited MBA programs to be offered not only at the home university but also in other countries and continents, making the MBA truly a global degree.

Kastelle says that as a lot of learning is social, the challenge for business schools is to ensure that any technology utilised can replicate that in an online or virtual way. It’s something he’s working on in terms of ‘micromaster MOOCs’ for other study areas, and which may eventually end up in UQ’s MBA.

In recent times, the use of simulation and other techniques has helped MBA students to become more engaged with capstone and advanced-level topics. In future, seamless connectivity via an improved internet and data transfer will assist MBA programs tremendously, enabling course conveners to connect with students who cannot access the MBA through a traditional mode. “By reaching out to untapped sections of the society, the MBA will become a truly inclusive degree for all,” Ahmed says.

Business ties

Not surprisingly, business schools strive to form deep and fruitful relationships with the business world. For example, the curriculum and content of the Flinders MBA are industrydriven and supported by a number of industrybased activities. In addition, the Flinders MBA is supported by a very active industry advisory group. This advisory group is led and managed by industry experts who provide input and guidance to the Flinders MBA program.

The Flinders MBA aims to further close the gap between student and industry by providing industry partnerships, and placement of students in real organisations. Flinders’ MBA has links with over 200 organisations in Australia to facilitate student placements. Involvement in the New Venture Institute at Tonsley Park encourages students to start new businesses and promotes entrepreneurship with innovative ideas. Instructors at Flinders Business are also actively participating in a number of industry bodies as members, advisers and experts.

For UQ’s Kastelle, the key is to embed MBA learning into the workplace. The UQ MBA’s capstone subject, tackled at the very end of the course, is an industry project that runs for the duration of a semester and allows students to work with an actual business or not-for-profit. “It will be with an organisation that has come to us and said, ‘We’ve got this strategic problem. Can you provide some help?’ Students will work in teams and come up with recommendations for those partners.”

Similarly, alongside the typical business advisory boards and committees, Sydney’s MBA allows students to “go deep” into businesses, offering a capstone subject that requires students to partner with an organisation and design a minimum viable product for them that reflects something on their strategic horizon. The organisation must have the budget for it and be prepared to invest in it.

Making a choice

What are some key considerations for a student looking to undertake an MBA?

Ahmed says there are three competing forces that should make an MBA program more attractive to prospective students: appropriateness of the program, accreditation, and affordability.

Accreditation plays an important role in MBA admission because an accredited MBA delivers a quality program with high impact on students’ leadership and managerial development. As of December 2017, only 86 business schools in the world held all three major accreditations, famously known as ‘triple crown’ accreditation: AACSB, EQUIS and AMBA.

The Flinders MBA is currently pursuing the prestigious AMBA UK accreditation in 2018. If successful, it will be the third university in Australia, and the sole university in South Australia, to have an AMBAaccredited MBA program. Accreditation by the AMBA or any other accreditation body is incredibly rigorous. If a university has seriously sought accreditation with an accreditation body such as AMBA, students can be assured that their MBA program has been subject to careful scrutiny of key qualitative and quantitative criteria.

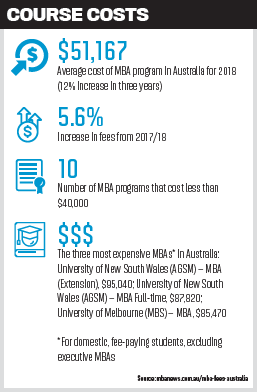

Affordability is another consideration, as some MBA programs charge exorbitant fees, whereas others are reasonable and deliver value for money. In the last few years, MBA fees in Australia have increased by 12%, therefore it is prudent for prospective students to compare MBA programs in terms of their reputation and accreditation status.

The chosen MBA must show evidence of being able to equip students with tools and techniques to lead and manage businesses and industries. Prospective students can use publicly available data and information – for example, Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) data and the Good Universities Guide – to compare business schools and their offerings, including elements such as overall experience, good teaching, student support, learner engagement, and skills development.

Prospective students should also consider why they want to pursue the MBA, and in particular, which MBA will be suitable for them.

There are currently approximately 1.2 million MBA applicants for 22,000 business schools worldwide. The volume of applicants attests to the continued interest in MBA programs. However, students should assess their current and future professional goals, the industry they wish to work or initiate business in, and how they would like to contribute towards business and society by taking up the MBA program.

“The prospective student should speak to the MBA director or responsible persons and expect to find him or her to guide them in their MBA aspirations,” Ahmed says. “In addition to guidance, by speaking directly to the MBA course director and the lecturers, a prospective student can get a feel for the conscientiousness of the staff, their enthusiasm, and their sense of accountability to students.”

Ford says the future of the MBA is bright, but business schools must adapt to changes in the business world and new expectations from students. “No one will throw away the nomenclature MBA, because it’s globally recognised,” he says. “However, increasingly no two MBAs are the same, so it’s a case of prospective students going to information sessions and attending taster classes. See what the other students are like and what sort of questions they are asking. The top programs are all very good, but they are very different in the way they go about things, so make sure you find the one that best suits your needs.”