How many definitions can there be?

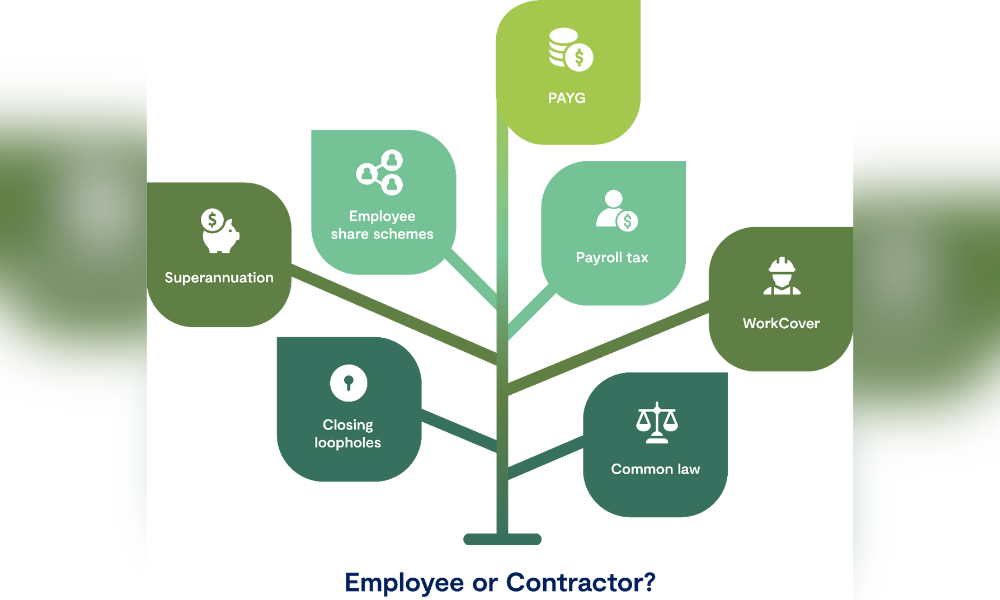

The answer? Seven. Especially when you allow for the inevitable collision of employment law with tax law in Australia.

In this article, we will break down the daunting task of identifying the most common challenge: correctly identifying the employee/contractor relationship. We will then guide you through the minefield that is the intersection of common law, the Fair Work Act, PAYG, FBT, superannuation regimes, and, of course, Workers’ Compensation (which varies by state).

The recent Closing Loopholes legislation has sent us back to the future by reinstating the multi-factor test for distinguishing between an employee and an independent contractor.

For now, we have two definitions of employee. One for common law and another when considering the operation of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). Let us take a closer look at both.

Before the landmark High Court cases of Personnel Contracting and Jamsek in 2022, case law required examining the “real substance of the relationship,” not just what was described in the contract. This was known as the “multi-factorial test,” where courts considered various factors and circumstances, with the contract’s description being just one of many factors.

Many clients were regularly caught out by this, engaging individuals as sole trader contractors but treating them like employees. This often led to unpaid liabilities for leave entitlements, superannuation, and penalties if the multi-factorial test classified them as employees at law. The result? Confusion and uncertainty for commercial operators was widespread.

Then, for a brief moment, a glimmer of hope emerged. A new era of case law started to develop – Skene, Rossato, and finally, Personnel Contracting and Jamsek heralded in the era of “contract is king.” As long as the relationship was clearly defined in the contract as that of a principal and independent contractor (and not deemed a sham), the contract was determinative and there was no need to look beyond the four corners of the contract.

This sigh of relief proved short-lived. In September 2023, the Albanese government introduced the Closing Loopholes legislation, bringing back the complexities of the multi-factorial test through its new “employee” definition.

The Closing Loopholes legislation makes significant and numerous changes to the Fair Work Act, including setting a new definition of “employee” and “casual employee.”

Whether a person is an employee (as opposed to an independent contractor) will depend on the real substance, practical reality, and true nature of the relationship. This requires looking at the whole relationship between the parties including the terms of the contract and how it is performed in practice.

Businesses engaging contractors must now consider this new Fair Work Act definition and seek advice to ensure compliance.

There are limited exceptions to being covered by this new definition, such as individually engaged contractors who earn over the contractor high-income threshold (currently undetermined) can “opt-out” of this definition. However, they can also revoke this opt-out notice, causing confusion and an administrative nightmare for employers.

For casuals, the new definition states that an employee will only be a casual employee if there is “no firm advance commitment to continuing and indefinite work,” which also includes the real substance, practical reality, and true nature of the relationship.

Some relevant factors as to whether the true nature of the relationship is casual or not are:

Clear and carefully considered terms in a contract remain critical in light of the new amendments to the industrial landscape. Employers must however, also turn their minds to how the relationship is permitted to operate in practice and ensure that it is consistent with the contract.

In Queensland, the legislation uses the definition of a “worker” instead of employee.

A worker is “a person who works under a contract and, in relation to the work, is an employee for the purpose of assessment for PAYG withholding under the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cwlth), schedule 1, part 2-5.”

Breaking this down, the first element is that it must be a natural person who works under a contract. The interposition of a corporate structure will take the arrangement outside of the definition, unless it’s a sham.

The key wording for WorkCover is whether someone is engaged under a contract for services, or a contract of service. A contract for services usually signifies an independent contractor relationship, where services are offered to the world at large (e.g. an electrician). Conversely, a contract of service indicates an employment relationship, where you are serving an employer on an exclusive basis and is characterised by a high level of control or the reservation of the right to control the way in which work is performed. (e.g. an electrician engaged to perform work for one company).

This definition applies only to individuals, capturing sole trader independent contractors.

You must not assume that only your employees on the payroll are covered by your relevant policy, as it may extend to cover any individual sole traders. WorkCover coverage can also be a factor in the multi-factorial test to consider whether a person is an employee as a matter of law.

Payroll tax is levied against ‘taxable wages’, which include certain payments made by an employer to an employee. While each state may have its nuances, generally, the following individuals are considered “employees” for payroll tax purposes:

In respect of the last point, if the working relationship is genuinely that of principal/contractor, while the starting position is that payments will be caught as taxable wages, there are several possible exclusions. We will touch on these in part 2.

The main takeaway is that even in the case of a principal-contractor determination, payroll tax does extend to cover payments to contractors under a “relevant contract” (in each state but WA).

Traditionally, the “multi-factorial” test was employed in common law analysis of the employee-contractor distinction for payroll tax purposes. However, we are now guided by Personnel Contracting and Jamsek, a worker’s status is judged primarily by reference to the contractual terms.

The rest…

Understanding PAYG, SG and FBT

The term “employee” isn’t defined in the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (TAA), leaving its interpretation to common understanding. This ambiguity has historically made the ATO’s position for pay-as-you-go (PAYG) withholding, superannuation guarantee (SG) and fringe benefits tax (FBT) somewhat unclear.

In December 2023, the ATO issued Taxation Ruling 2023/4 (TR 2023/4) to clarify who qualifies as an “employee” for PAYG and SG purposes. This ruling aligns with common law and payroll tax positions, emphasising the importance of written contracts in determining the nature of employment arrangements, while considering the overall relationship between parties.

Issued concurrently, PCG 2023/2 provides an outline of the Commissioner’s intended approach to compliance in this space.

While the ATO guidance is primarily based on the High Court’s current position, the objective of the FWA amendments is to instead reverse the impact of those decisions.

Like the TAA, under the Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) (SGAA) “employee” takes its ordinary meaning. While TR 2023/4 provides helpful guidance, there is an expanded definition of employee under the SGAA that captures various engagements that will apply only for SG purposes. The SGAA expands the definition of employee for superannuation to capture those who are paid wholly or principally for their labour as an employee for superannuation purposes and superannuation contributions must be made on their behalf. That is, irrespective of the fact that the relationship may be one of principal-contractor for PAYG and/or payroll tax purposes.

SG-specific ATO rulings have been under review since Personnel Contracting and Jamsek.

A fringe benefit is a benefit that is provided to an employee or their associate, by their employer (or an associate of the employer, or by a third party under an arrangement with the employer), in respect of that employee’s employment.

For FBT purposes, an employee is a person who is/has been entitled to receive salary or wages. Importantly, FBT captures current, former and future employees (that is, an individual who has accepted employment).

The definition of “associate” includes a relative, partner, spouse, child, or friend of an employee. Generally, only benefits provided to employees under formal employment constitute a fringe benefit, while benefits given to volunteers and contractors are not typically subject to FBT.

For a scheme to qualify as an “employee share scheme” (ESS) for tax purposes, the ESS interests must be issued to employees or their associates (including past or prospective employees) in relation to the employment of those employees. The guidance provided in TR 2023/4 is relevant here.

The question remains – which of these is relevant and how do you know which definition to give primacy to? The answer – all of them. Companies often separate their human resources, payroll, and risk and compliance departments, which can make it difficult to have a holistic view of the workforce. However, these key staff must come together and apply their collective knowledge of the definitions of “employee” and work together to make sure that compliance with employment, taxation, and superannuation is consistent. In other words, don’t do it on your own, this stuff is complex!

Failure to do so may mean that, come yearly audit/review time, non-compliance could result in civil penalties under the Fair Work Act and fines under the various taxation legislation. Civil penalties under the Fair Work Act have recently increased to a maximum of $469,500 for each contravention for companies, or up to $4.695 million for serious contraventions. It’s worth putting in the time and effort to get it right from the beginning.

Elizabeth Allen is a special counsel specialising in commercial tax, Caitlyn Wessels is an associate specialising in employment law and safety, and Emma Carr is an associate specialising in commercial tax, all at Macpherson Kelley in Brisbane.