Report highlights prejudice – but employers are missing out, says Sydney academic offering tips for HR on how to benefit from older workers

More than three-quarters of workers older than 50 think their younger colleagues harbour extremely or reasonably discriminatory views about them.

In addition, a large majority, 83%, say they are generally undervalued, and 78% feel that younger generations get more attention for the same effort.

These grim findings are contained within the Gen Seen Report 2024, part of the Australian Seniors Research Series commissioned by insurer Australian Seniors.

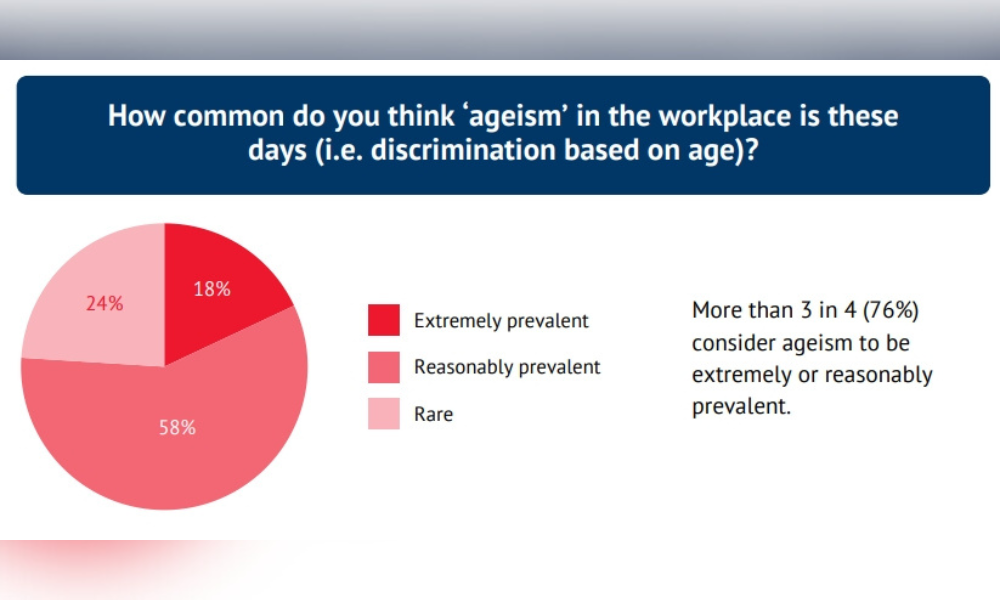

More than 5,000 Australians aged over 50 were interviewed for the survey. About 58% of participants considered ageism to be reasonably prevalent at work, and 18% said it is extremely prevalent. Nearly a quarter said it is rare.

But it’s not all bad news: Joanne Earl, a professor of psychology at Sydney’s Macquarie University, told HRD that organisations with older workers may discover they have deeper resources than they realise and boost their reputations as coveted employers.

The trick, she said, is to offer workplace flexibility, opportunities for mentoring and support in transition to what comes after work.

“If organisations really cared about their employees – the whole person – they’d be doing what they could to make that transition as supported as possible,” she said.

The survey showed employers of older workers may have good reason to not consider them first in line for advancement. More than half of respondents (54%) said they are happy to hold a steady career course, whereas 40% admitted they are winding down. Only 6% are building up for something better. As to their ambitions, 49% have none. They value their job for its security.

To Earl, it looks like a chicken or egg situation.

“It could be that [employers] believe individuals aren’t interested in promotions or being considered for other opportunities, and so they don’t engage them in conversations,” she said. “But I would say this is an opportunity for individuals to take agency of their own careers, and to plot a course that sets the way forward for themselves and, at some point, engages their employer.”

There are plenty of go-getters among the 50-plus. About 19% of those surveyed are keen to roll their sleeves up and mentor colleagues. To do it, they need to offer their services. But do they have the confidence to speak up? And will they be heard?

This is where HR teams can uncover wealth in their organisations, Earl said, by asking the right questions during regular career development sessions.

“These discussions should happen across the lifespan,” she said, with older workers included no less frequently than graduates.

Managers can be creative about implementing mentoring programs, she said. Twenty percent of employees might want to be mentors, “but there’s probably another 20% who want to focus on being an expert in a particular area, or another group who have valued clients they want to develop deeper relationships with,” Earl said.

Such transitions can offer flexibility and a better work-life balance if they include a transition from full-time to part-time.

But Earl has a warning.

“One of the fundamental things that underlies all of these ideas is the importance of trust,” she said. “When I ask employees why they don’t have conversations with an employer about going part-time, overwhelmingly the answer is ‘Because when I say I want to go part-time, they hear that I want to retire, or they hear that I want to be made redundant.’”

Flexibility is important to older workers, with 37% placing a better work-life balance among their primary ambitions. Earl isn’t surprised. She found a similar result in research she conducted for a financial services provider.

For some, the idea of not working at all has plenty of appeal. As they approach retirement, however, older workers need to test their expectations about what happens after their last day at work. People who have more say about how and when they exit work will more easily adjust to retirement, Earl said.

“People think about retirement as all-or-nothing,” she said. “It’s really about that later career stage and what you want that to look like. If people only have a vague idea of how they want to improve their flexibility, an organisation can’t really make any sense of what the alternatives are that they might offer.”

HR departments can help, she said, by allowing more flexible work patterns to help people to reach their career aspirations, but not necessarily in just a full-time contribution.

It is important that individuals feel they have agency, Earl said. To find better satisfaction at work, a worker might do their own reconnaissance to identify what the organisation can offer older employees.

“It might mean having a look at other older employees and their career paths, and planning ahead,” she said.

Does the worker want to continue their career with that organisation longer term or do they want to create their own opportunities? When asked about their ambitions, 9% of respondents said they would like to start a business, found Australian Seniors.

A company that can get the best out of workers of all ages will have no trouble recruiting, Earl said.

“If you get a reputation as an organisation that genuinely cares about employees and offers great opportunities across the lifespan, I mean, who wouldn’t want to be known for that? People would go into that organisation at different points in their career with a view that they’ll be making a contribution until the time is right for them to part ways.”