In 2014, businesses face unique and unprecedented challenges. Has HR positioned itself in the most effective way to meet these challenges? Iain Hopkins weighs the pros and cons of the dominant Ulrich model and looks at possible alternatives

In 2014, businesses face unique and unprecedented challenges. Has HR positioned itself in the most effective way to meet these challenges? Iain Hopkins weighs the pros and cons of the dominant Ulrich model and looks at possible alternatives

Organisational design is usually a strong calling card for senior HR professionals. In conjunction with other business leaders, it is often HR that designs and implements the structures within its organisation. But what about its own backyard? How has HR structured itself in order to deliver its services to the business? And perhaps more importantly, are those structures working in today’s business world?

ULRICH DOMINATES

According to The Next Step’s HR Viewpoint research paper from 2012, 53.9% of HR professionals in Australia and New Zealand work in the Ulrich model, and a significant 81% of HR professionals use that same model in companies of 1,000 plus employees.

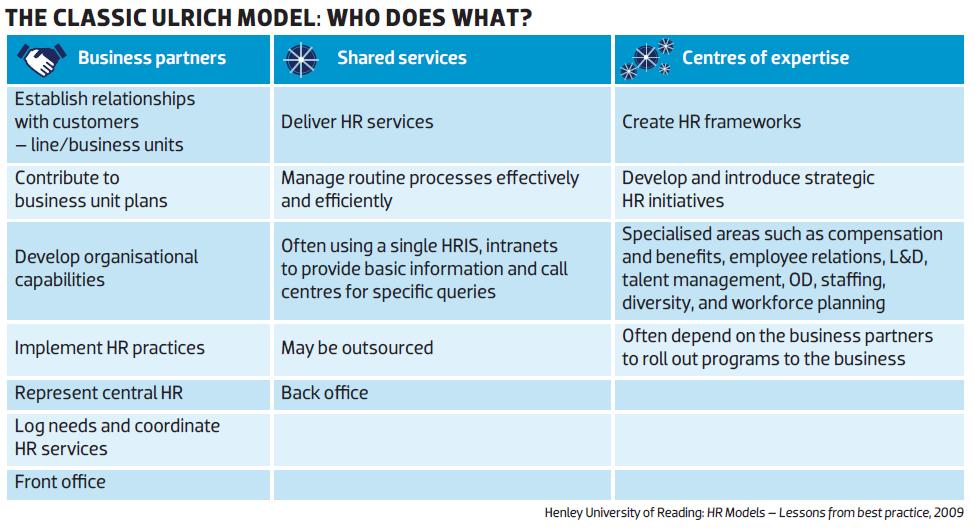

Born in the late 1990s, the model that eventually adopted his surname came about when Dave Ulrich and his colleagues Wayne Brockbank and Jon Younger articulated how the modern HR organisation could be organised into shared services, centres of excellence (or expertise), and business partners.

It suited the evolving role of HR in business as the profession moved from transactional tasks to higher-end strategy.

“The Ulrich model probably does the best job of defining roles and responsibilities across those generalist areas and the specialist centres of excellence,” says David Guazzarotto, CEO, Future

Knowledge.

Yet, as the word ‘model’ suggests, this is not set in stone. According to Ulrich himself, it was always intended that this model would evolve over time.

The Ulrich model has been criticised for looking fine in theory but being less effective in reality. David Grant, director, The Next Step, likens it to the engine of a car: you can have components of it that are humming along well, but if all the interrelated parts are not working properly it can create problems. “In a lot of companies these models are not well embedded, and they are still relatively immature,” he says.

Indeed, Ulrich’s effectiveness depends on a few critical factors. Firstly, there is a challenge around convincing business divisions to utilise HR shared services, and a corresponding risk of ‘doubledipping’. “There’s a history of employees going to shared services, not getting the response or assistance they need, and then going to the business partner for the same response,” says Grant.

There’s also a secondary challenge around whether or not the business partners of old actually have the motivation and/or capability to be truly strategic business partners.

“Is their toolkit one that is aligned more to the day-to-day operational functions – compliance – or do they have the tools to play in that upstream space?” Grant says. “The feedback we’re hearing is there’s such a strong demand for business partners who are business savvy.”

Guazzarotto echoes this and says the acceptance, or otherwise, of HR business partners within business units comes down to perception. He suggests this is a legacy of HR having a PR problem.

“I think HR is still grappling with operations teams who view HR as administrators. For example, they still see it as part of HR’s remit to change an employee’s personal details and handle those basic tasks. They are reluctant to take that on themselves and still see it as the primary role of HR. So part of this is continuing to educate the broader business and operations folk about the strategic value HR can bring.”

A further challenge is what Grant calls “the old argy-bargy” between the centres of excellence and the business partners. “Is the dog wagging the tail or the tail wagging the dog? Are business partners informing the centres of excellence on what their business needs are, and the centres then designing and delivering services accordingly, or are the centres of excellence saying, ‘Here’s the program for you to roll out across the business’?”

Consultation and communication between business partners and centres of excellence is obviously critical to this model working.

“The whole intent of the model is it achieves some economies of scale and productivity gains, while having as lean a centre as possible. Increasingly, a trend is having fewer initiatives and programs being designed in-house within individual business units or centres of excellence and instead leveraging third-party specialists,” Grant says.

“It potentially provides greater visibility, across the whole organisation, of what the requirements are, and then taking the opportunity to use off-the-shelf programs and tailoring them to business units,” he adds.

If handled poorly, however, Grant warns that removing authority from business units can create friction and complaints about a loss of control, as well as grumbles of discontent about the new, poorly tailored solutions being delivered to them.

The Ulrich Model : Who Does What? (Click for larger picture)

LOOKING AT THE MACRO PICTURE

Before considering alternatives to Ulrich, it’s worthwhile placing HR service delivery in a wider context and establishing why change might not be a matter of choice. Demographic changes, advances in technology and the changing demands of business are all major considerations forcing the issue.

The main demographic issue is Workforce 2020. This will see a multigenerational workforce in place over the next five to 10 years. Guazzarotto says this factor alone will impact on HR quite substantially.

“Being able to get beyond the transactional support and understand what’s driving the different types of workers, being able to look forward, to be future-oriented, rather than just looking to the present and the past, will be very important for HR,” he says.

It’s also important to note that, although retirement was delayed for many older workers following the GFC, the baby boomer exodus will soon pick up. In the US, for example, the average age of a CIO is 57. This means there will need to be a generational shift in senior leadership in the next decade or so. Again, HR has a critical role to play.

Increasingly, the CEO is looking to get the same level of trusted advice and support from their HRD as they would from their CFOs on the finance side of the business. To do that, those heads of HR need to be able to get away from just dealing with the operational elements.

It’s telling that many of the world’s most successful HRDs (GE’s Bill Conaty; Mary Anne Elliott of Marsh) have worked in line operations – such as sales, services, or manufacturing – or in finance.

“CEOs are looking for support on things like: where will we get our talent from in the years to come, how will we address the shortages, and how do we engage and retain younger workers who don’t really see themselves as being defined by working for one organisation? These are major strategic challenges that are driving the changes to HR and forcing them to operate more strategically,” he says.

There is also the productivity issue for all employees, including HR. “There’s no question that in the last few years, as productivity has become a focus across businesses, HR has been asked to review its headcount and make a contribution to that productivity. That has typically resulted in a review of HR operating models and a move to greater centralisation,” says Grant.

On the technology front, there is a growing appetite among employees and managers for direct access to self-serve systems. “There is increasing acceptance from middle managers that a big part of their remit is supporting their people and being aware of talent management challenges. They are also saying, ‘We need better tools; I want to be able to directly engage with providing feedback and developing my people and I don’t want to have to outsource that to someone internally’,” says Guazzarotto.

Indeed, the digital revolution is already having a major impact on HR. “Digital equals data, and workforce data will underpin commercial data to allow HR to move away from HR metrics of static post-event data, to measures that have commercial outcomes,” says Marc Havercroft, talent sales leader, Mercer. “This will be the first step towards managing the workforce as an asset. The principles applied to the other main commercial assets on a balance sheet can be used for the workforce, enabling better predictive commercial control of the workforce.”

Mercer refers to this as ‘long data’, but Havercroft warns that the real task is to take big data and ask the right questions of it. “Your workforce metrics and analytics are only as good as the questions and resulting data that generated them – otherwise, the metrics and analytics will only produce ‘data smog’,” he says.

Guazzarotto says it’s important to not put the cart before the horse. In other words, while technological change can be overwhelming, it should not be dictating the shape and structure of HR departments. “Too often we’ve led the change with the technology itself rather than looking at the operating models and how the people management functions in organisations can be more effectively handled. What’s tended to happen is the technology has pushed in as the driver of the change, and there’s naturally a lot of resistance.”

ALTERNATIVES

So how else can HR deliver its services to the business? With HR transactional elements removed from the equation – or at least placed on the backburner – Guazzarotto suggests it’s time to tether HR back to what its lead function is. He notes a recent reluctance by some organisations to brand their HR teams as HR.

“They are looking for better descriptors of what the function does,” he says. “They are starting to say, if this function is about people & culture or about talent & development and those types of strategic goals, why don’t we call it that? It ties back with that PR issue HR has with operations folk – they still perceive it as transactional.”

Companies are responding in a couple of ways. One is to split HR in two and pare off that transactional piece and give it to finance as an adjunct to payroll and other shared services.

“That’s giving a signal to the organisation that what you thought of as HR doesn’t exist anymore. We are now a people & culture function, which is focused on developing the next generation of leaders, on building a more agile organisation, and providing that deep level of support to the business at strategic level,” says Guazzarotto.

Another approach is to retain HR business partners but, instead of having them as generalists, make them more specialised. Where once business partners would sit in a business unit and be broadly responsible for connecting that unit with specialists when needed, there’s a move towards seeing a business partner as a specialist in recruitment, talent development, or engagement, and that business partner potentially then having direct responsibility for that piece across a whole organisation.

“That’s come with the benefit of now having that Ulrich-style model as the frame of reference, where it’s accepted you’ll have HR people sitting alongside you and dealing with issues hand in hand,” says Guazzarotto.

BECOMING AGILE

Two au courant words right now are ‘agility’ and ‘disruption’. The two are interconnected: agility is a response to what has been called ‘the age of disruption’. It means there’s a growing need to be responsive, and to be able to adapt quickly to change.

‘Agile’ was born out of IT teams in the 1980s and 90s. Inundated with projects, under-resourced, and under immense pressure to provide a return on significant financial outlay, it was quickly evident that a better way of doing business had to be developed. There are synergies with HR’s current position.

In perhaps the clearest sign yet that the shift to centralisation is spreading, ‘agile’ models are now being deployed in HR departments. Centralised pools of generalists are being created to work on a ‘supply and demand’ model. Rather than being embedded within divisions, the HR generalist sits in a centralised pool. Each business division is required to put forward a business case to use these services: “We have this problem; we have X number of people impacted – can you help?” HR professionals are then assigned to manage the initiative. These might be assignments that would last several years if it was a major change or transformation; other assignments might only last a few months.

“We’re just starting to see the emergence of those structures in a couple of large-scale businesses,” says Grant. “It’s not just HR – it might be across a range of job families, like the finance division, for example. It’s moving more towards a professional services consultancy model built around utilisation.”

This agile model also matches changes in general org design, which is moving away from deep hierarchies towards flatter structures and more cross-team collaboration.

“The ability to form a team around an issue, who may come from different parts of the organisation or may be geographically dispersed, and then collaborating to resolve the issue and then disbanding again, is a large part of agile teaming,” says Guazzarotto.

There are obvious benefits for HR teams operating in this model. The broad business exposure it provides to HR practitioners working in diverse business units provides valuable learning experiences. However, it does pose an interesting question around succession. What will succession look like for people working in those models? How will performance management be impacted?

One response, Grant says, might be to put in place a business and/or HR manager wherever the piece of work needs to be done, to provide guidance and post-assignment reviews. That person would contribute to the practitioner’s performance review in terms of how they delivered against that assignment. Secondly, HR practitioners might be assigned mentors to oversee their development.

“It requires moving away from hardline reporting where your direct manager is doing your performance review annually, to several people contributing to your review in more of a matrixed way,” suggests Grant.

HR also needs to address, both for themselves and for anyone else working in an agile team, the interpersonal and communication challenges associated with working ‘at distance’ from colleagues who may be geographically dispersed.

MAKING THE CHANGE

For any HRD considering a shake-up of their model, there are some critical steps to take.

The need for speed in restructuring is often at the cost of robust consultation with employees, suggests Tanya Perry-Iranzadi, director, Company Restructure. “When employees are involved in shaping their destiny they feel empowered and engaged, not ‘done to’, which is too often the case. The current restructuring practices of companies need to be challenged and the actual employment relations approach examined.”

Secondly, consider undertaking a test prior to implementation.

“Testing structures or models in a defined area of the business, and ironing out the bugs prior to organisation-wide implementation, makes sense and provides credibility to the implementation,” says Perry-Iranzadi. “Often multinationals use Australia as a testing ground for international changes due to our small, mature market. Selecting the right test area is the challenge. I’ve had success in choosing a manager or area that is pro the change and one that is against the change to ensure a range of dynamics are covered.”

Finally, the change initiative needs to be sold to the business. Employees and business leaders alike need to know what’s in it for them and for the future success of the business. People are tired of change for change’s sake.

“The role of the HRD is to channel thought leadership and authentically sell the initiative, which is way beyond an organisation announcement. How good are you at selling? How convincing are you? Do you naturally come across as authentic and believable?” Perry-Iranzadi concludes.

This feature is from the August issue of HRD Magazine. Download the issue to read more!