'If there was a perfect solution, we would've come up with it by now,' says comp expert after Air Canada CEO makes headlines

Earlier this month, Air Canada made headlines when it was revealed CEO Michael Rousseau was paid $12.38 million in 2022 — a 233-per-cent increase compared to the previous year.

This came just two years after the airline’s managers received $10 million in COVID-19-related bonuses, despite mass layoffs.

According to data from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the average CEO pay for Canada's top 100 listed companies in 2021 was $14.3 million. That balance is a hard line to walk for HR, and one which often ends in PR issues.

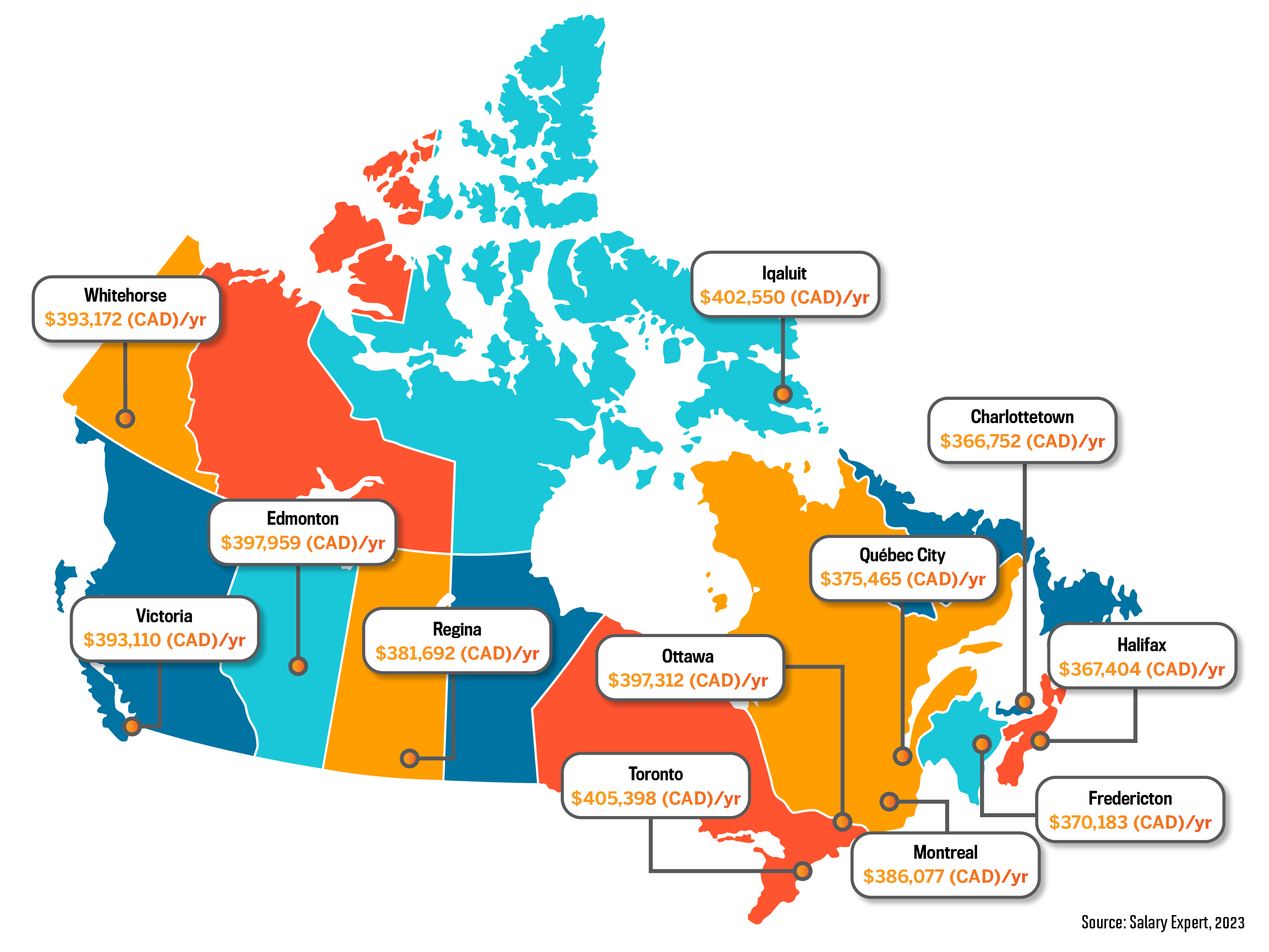

Executive compensation can be a sensitive issue for HR to deal with, given the optics and possibility of employee resentment. So how does it find that balance?INSERT INFOGRAPHIC ONE: Title: Average bonus in Canada by city HRD spoke to Barry Hoffman — an experienced non-executive director, former chief people officer, and member of several remuneration committees – about the nuanced role HR leaders play with CEO compensation.

HRD spoke to Barry Hoffman — an experienced non-executive director, former chief people officer, and member of several remuneration committees – about the nuanced role HR leaders play with CEO compensation.

“In the listed PLC environment, it’s usually the remuneration committee of the board of directors that will approve C-suite bonuses based on the recommendations of the CEO at the end of the performance period,” Hoffman tells HRD. “But before that happens, the committee would have been involved in target setting at the start of the performance period to make sure that targets are achievable and that different scenarios are modelled – as well as delivering a pay-out that’s appropriate and in line with the original intent of the scheme.”

Hoffman tells HRD that, ideally, the chief people officer is part of that review process in order to provide some objectivity and offer up a broader perspective for the committee – a group which typically meets once or twice a year.

“Most bonus schemes should have objective, financial and non-financial, measures, and this makes it easier to define the outcomes,” he says. “If bonus schemes contain elements of personal performance, then the determination of the bonus becomes more subjective and HR can end up playing the role of referee.”

Canadian publicly traded companies are required to disclose executive compensation information in their annual proxy statements filed with the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA). This information includes details about the CEO's salary, bonus, stock options, and other forms of compensation.

“A chief people officer or a reward director will certainly be instrumental in devising bonus plans, helping with calculating and communicating the CEO’s recommendations of C-suite bonus outcomes to the remuneration committee or the board,” adds Hoffman. “And, ideally, they’ll be part of the process of signalling the likely outcomes as the performance period progresses. So, often, the results of a bonus scheme come as a complete surprise to the recipient and HR can certainly help to smooth any mismatch in expectations.”

One of the biggest mistakes in bonuses is trying to retroactively fit the result because the formulaic outcome doesn’t represent their view of what’s fair – with Hoffman adding that people often confuse effort with outcome. In order to mitigate this, it’s essential that employers are wholly transparent when awarding big bonuses – trying to hide pay-outs will only draw ire.

“The best thing for HR to do is make sure bonus schemes are transparent and properly communicated with regular progress updates – especially long-term incentive plans,” says Hoffman. “The more the outcomes match the expectations, the less there is likely to be negative fallout internally. It’s harder to control the media reaction.”

However, an organization with a strong purpose, that puts people before profit and contributes to wider society, should see be able to talk about the broader, positive impact of the business in which everyone case share the fruits of success, according to Hoffman.

“And a great bonus outcome is a result of great outcomes for the business, its customers and the communities it operates in.”

So, just how much is budget considered when allocating bonuses? According to Hoffman, it’s more a question of the wider stakeholder experience rather than budget when deciding who gets paid what - bonuses are often, and should be, self-funding. After all, greater profits mean bigger bonus pots.

“However, if your customers or shareholders have had a difficult year, despite strong business performance, and therefore potentially large bonuses, boards may want to think twice. When setting bonuses at the start of the performance period, convention usually has a role to play. CEOs of FTSE business will have their pay benchmarked and so a bonus of 200% of salary might be the convention in a particular sector. This approach tends to flow down to the C-suite.”

The main issue that the media seems to pick up on is the size of the bonus – seeing the high figures as outlandish. However, that’s not an entirely fair assessment. Earlier this year, the UK Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) proposed the removal of bonus caps on banks and investment firms – a cap which currently rules that PRA-designated firms don’t exceed 100% of the individual’s base pay. It’s not necessarily designed to curb big bonuses, rather to prevent excessive risk-taking in the short-term.

But what constitutes an “excessive bonus”? Well according to Hoffman, that’s almost impossible to answer – it’s all subjective.

“The obvious answer is ‘one that isn’t deserved’,” he tells HRD. “But what is deserved can be subjective and certainly employee activism, shareholder proxy organizations and the media can decide that a bonus is extravagant without knowing the detail of the bonus plan, the original intent of the bonus or anything other than some headlines.

“It’s impossible to say what extravagant is and, I for one, wish we could have a sensible debate about this without headline-grabbing rhetoric taking over.”

According to recent data, the top 100 highest-paid CEOs now make 243 times more than the average employee.

The underlying issue for HR leaders is balancing the need for executive remuneration with internal and external sentiment. Practitioners are also responsible for ensuring that the executive compensation plan is in compliance with applicable laws and regulations, including tax laws, accounting rules, and securities regulations.

It’s preparing for those unintended consequences that Hoffman advises. For example, he tells HRD that you might find high attrition after the bonus payday or people leaving in the first few months of a performance period if they think the bonus is not going to be achieved.

“Managers, and HR people, haven’t really found an alternative to bonus that is perfect,” he adds. “What I do know is that in successful companies that regularly pay strong bonuses, there is little complaint. When times get tougher, that seems to be when the rot starts to set in. If there were a perfect solution, someone probably would’ve come up with it by now.”