'We're seeing more of a push at the bargaining table for wage increases, as well as cost-of-living allowances'

Another day, another union dispute. The recent spate of industrial actions across Canada has led to increased concerns for HR leaders and their employers – specifically in regards to how best to deal with unions and their representatives.

Unions are being quite aggressive in their wage demands given the presence of inflation, according to Lorenzo Lisi, partner at Aird & Berlis.

“Unions want higher wages for their members and so we’re seeing more of a push at the bargaining table for wage increases, as well as cost of living allowances in case inflation continues to rise. Personal purchasing power is dwindling, and at the same time, employers are struggling to keep costs in check, with the uncertainty of a recession or economic downturn always a concern.”

Coupled with a talent market which has suffered from a severe labour shortage, HR leaders are struggling with both attracting and retaining top talent, which may lead some employers to seek foreign workers in order to plug the gaps.

Unions have been dominating the news streams of late. A prominent dispute involving collective bargaining took place between the Canadian men’s and women’s soccer team and the body that governs the sport earlier this year.

After the players threatened to strike over wages, Canada Soccer proposed a new pay deal that would see women paid the same as their male counterparts, The Guardian reports, with part of the statement reading: “Our women deserve to be paid equally and they deserve the financial certainty going into the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup.”

The dispute made national headlines – namely because it also chimed with International Women’s Day – but also because it shed light on a wider issue of best practice when dealing with potential strike action.

As Lisi tells HRD, there are two main components when it comes to union disputes – those that deal with the interpretation and administration of a collective agreement negotiated between the parties; and those that involve the formation and administration of a union, and issues which might arise during bargaining, including a strike or lockout.

“After a union has been certified, and negotiates a collective agreement with the employer, disputes that are not settled during the grievance procedure, and deal with the terms and conditions of that collective agreement are addressed internally through the grievance procedure,” says Lisi. “An arbitrator either appointed or consensually agreed upon between the parties, will adjudicate and determine if there has been a breach of the collective agreement.

“Disputes that deal with the formation or administration of union rights generally, and the process of collective bargaining, are addressed through provincial (and where applicable federal) labour boards, who will adjudicate complaints by either party under the applicable legislation. For example, across Canada, there are time limits for when a strike or lock-out can occur, that is, when the parties are in an illegal strike – or lockout position.”

For HR leaders, the art of negotiating with unions is a delicate one – trying to satisfy employee demands while at the same time showing budgetary restraint and dealing with the inevitable work morale issues that may come with tough bargaining and a possible work disruption.

Strikes or lockouts require enormous planning on both sides, from contingency strategy for employers, to how a strike will be conducted by a union. And while the vast majority of negotiations result in the parties coming to a collective agreement, labour disruptions do occur.

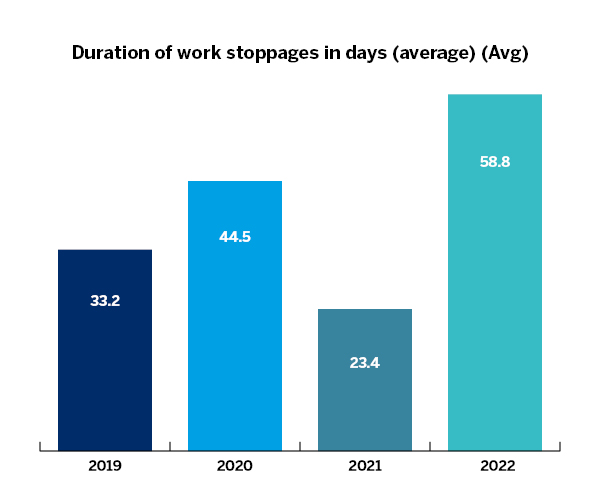

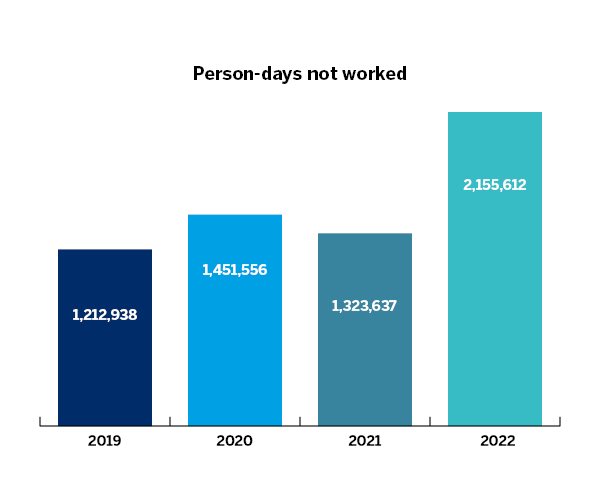

According to Statistics Canada, 222,595 workers were involved in strike action last year – accounting for 2,090,152 days not worked. The loss in productivity is only compounded by high inflation and ongoing economic uncertainty, leaving employers in a position where they have to make decisions impacting their employees which they may not necessarily want to make.

In these circumstances, it’s the role of HR to not only work towards a fair deal, but to heal the wounds that might come from a tough set of bargaining.

“Effective and contemporary labour relations rests with building respectful relationships,” says CHRO Dr Raeleen Manjak. “Each party has a particular responsibility, to either the employer or to the collective. When this is understood, there is an opportunity to work to create an environment that supports the reason that both parties are together, the employees.”

As Dr Manjak says, it’s good to remember that there are ways to manage the ever-changing workplace and that if conflict is not managed, it can be a costly and stressful distraction that ultimately undermines the successful labour management relationship.

“There are certain strategies to ensure that the discussion and decisions that are made are professional, clear, and communicated,” she tells HRD. “Communicate often. Remember, at times it is not about agreement, but understanding. This is the time to move forward from a place of respect. The labour management team is coming to this position in a place of leadership and therefore, they are called to show up in a respectful manner, to make decisions that are founded in respect, and have a level of accountability.”

One consideration? HR leaders and practitioners cannot form part of a union, even if they want to, says Lisi.

“With some minor exceptions, managerial and truly supervisory employees generally do not have access to collective bargaining under labour relations legislation in Canada,” he tells HRD. “HR practitioners fall into this category, given that they manage employees and have specific access to confidential information with respect to employees and the business. As such, they cannot be a member of a union which engages in collective bargaining ‘against’ an employer.”

So when should HR seek legal advice when it comes to dealing with a union? Well, it comes down to the specific issues brought to the table.

“Parties to a collective agreement are very familiar with how to deal with grievances under a collective agreement,” advises Lisi. “Where there are difficult issues, such as terminations or human rights claims, they may seek the advice or representation by a lawyer at grievance arbitration - which really is a ‘mini trial’. Many employers do their own bargaining, once a union is certified or for ongoing renewals of collective agreements which have expired. Sometimes, and most often where there is bargaining for a ‘first contract’, employers may use a lawyer. However, unions rarely use lawyers for bargaining.”

Having said that, Lisi says employers often seek advice if they have not had a union in the past, during the certification process.

“There are rules under labour relations legislation across Canada which protect the union organizing process, and impose rules on what an employer can and cannot do while a campaign is ongoing. They also address any ‘unfair labour’ practices by either side during the formation of a union, or the negotiation of a collective agreement.”

And while the collective bargaining system isn’t perfect, Lisi says it can and does work.

“Both parties have a responsibility. It should not be a combative environment, but one that starts from a place of understanding and respect,” agrees Dr Manjak. “The best ideas and ways to solve issues and challenges can emerge from the creative problem-solving that occurs to resolve conflict. Try not to view conflict from a negative perspective, but from one that can assist in accomplishing the goals and outcomes that need to be reached.”