The arbitrator found the request reasonable, given the circumstances

by Rhonda B. Levy, Barry Kuretzky and George Vassos of Littler

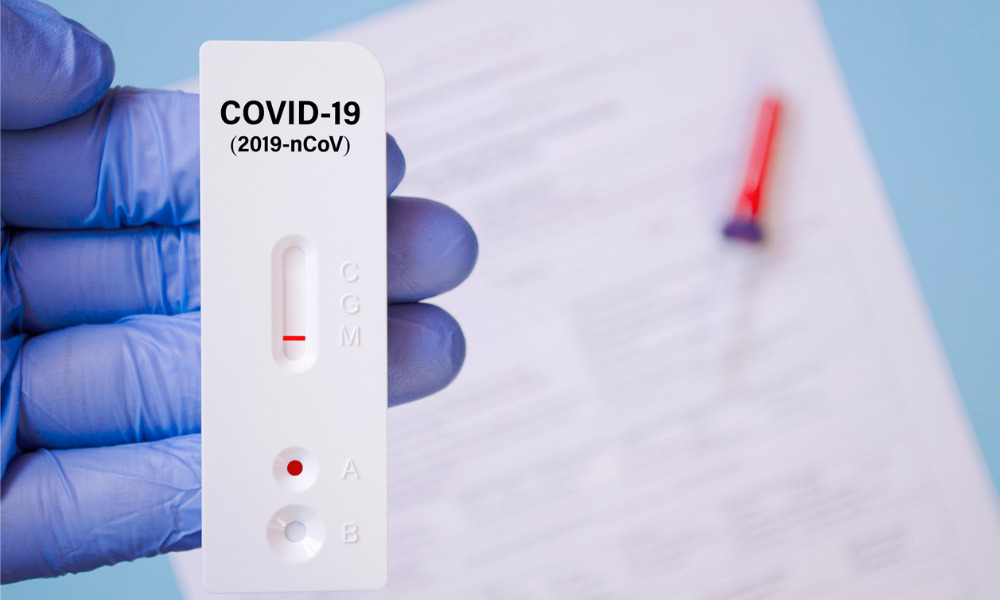

In EllisDon Construction Ltd. v. Labourers’ International Union of North America, Local 183, 2021 CanLII 50159, an Arbitrator in Ontario decided that when the intrusiveness of an employer’s compulsory Rapid COVID-19 Antigen Screening Program (Policy) was weighed against the objective of preventing the spread of COVID-19, the Policy was reasonable.

In February 2021, the employer, a construction and building services company, implemented the Policy as part of a pilot program led by the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH). The Policy required all individuals attending specified job sites to submit to a Health Canada-approved Rapid COVID-19 Screening Test (Test) to gain access to the worksite. The Test was administered by third-party qualified healthcare professionals on site twice weekly in accordance with MOH guidelines via a throat and bilateral lower nostril swab (more comfortable than a deep nostril swab). Swabbing could not be observed by anyone other than the healthcare professional. No personal health card information was taken or stored. Individuals undergoing the Test were required to provide their name and contact information for the purpose of notification if their results were positive. Information collected was only disclosed to and used by healthcare professionals and the employer’s management to communicate results to the individuals tested and local public health units. Employees were paid for their time spent testing and for the 15-minute period between testing and receipt of results.

The company also implemented the following health measures related to COVID-19 at the worksites where testing was conducted: requiring individuals attending the sites to answer a standard form screening questionnaire; providing handwashing facilities and hand sanitizer; providing appropriate Personal Protective Equipment, including masks; not permitting non-essential visitors and guests on job sites; scheduling work and start times to avoid overcrowding at site entry points; tracking and monitoring employees who reported illness, cold or flu-like symptoms, were in self-isolation, or who tested positive for COVID-19, and requiring subcontractors to also do so for their employees; and requiring individuals attending affected sites to have their temperature taken by a health professional before accessing the job site.

If a subcontractor’s employee refused to submit to the Test and was denied access, the subcontractor would make best efforts to reassign that employee to a different site where it performed work, but if no such site was available, the refusing employee would be laid off.

If the Test was negative the employee could return to work. If the Test was positive, the testing team would communicate the results to the individual and the company’s health and safety coordinator (HSE Coordinator); the HSE Coordinator would notify the company’s Healthline and begin contact tracing; any employees who were in close contact with the COVID-19 positive employee would be required to self-isolate; the local public health unit would be notified of the positive Test result; and the individual would be required to have a follow-up, confirmatory, lab based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test within 24 hours at a COVID-19 Assessment Centre, prohibited from accessing the job site pending the outcome of the PCR test, required to self-isolate until the result is available, and required to advise their employer of the result.

The company was bound by a collective agreement with the Labourer’s International Union of North America, Local 183 (Union). The Union filed a grievance against the company and a subcontractor, which was bound by a different collective agreement. The Union claimed the company and the subcontractor had violated the collective agreements by implementing the testing. The Union took the position that the Policy was an unreasonable exercise of management rights and an unreasonable company policy or rule. It argued that when weighed against employee interests such as the right to privacy and bodily integrity, the Policy was not a reasonably proportionate response to mitigate the risk of COVID-19 transmission in the workplace, which had been significantly reduced by less-intrusive measures (e.g., extensive pre-attendance screening, mandatory masking, physical distancing, enhanced cleaning), and the open-air setting in which employees work. Finally, to support its position, the Union relied on drug and alcohol testing cases that concluded that universal random testing for drugs and alcohol was an unreasonable exercise of management rights because the impact on employee privacy was more severe than the expected gains. The Union argued that the same principle should be applied in this case.

In determining whether the Policy was reasonable, the Arbitrator considered the circumstances of the public at large and in the construction industry and emphasized that his assessment of COVID-19 risk and his decision should not be made in a vacuum.

In conducting his analysis, the Arbitrator noted:

Finally, the Arbitrator noted that in another COVID-19 testing case, the analogy of drug and alcohol testing was rejected because controlling COVID-19 infection is not the same as monitoring the workplace for intoxicants: intoxicants are not infectious, and being intoxicated is culpable conduct but testing positive for COVID-19 is not.

In view of these considerations, the Arbitrator decided that when one weighed the intrusiveness of the Test against the Policy’s objective of preventing the spread of COVID-19, the Policy was reasonable.

EllisDon provides support for employers that wish to implement compulsory rapid COVID-19 testing. Such testing may be considered reasonable if the nature of the workplace is such that the risk of COVID-19 transmission is real, there is risk of transmission to the public, and steps are taken to protect the privacy and dignity of those tested.