From investigations to mental wellbeing, employers have a duty of care in protecting their people

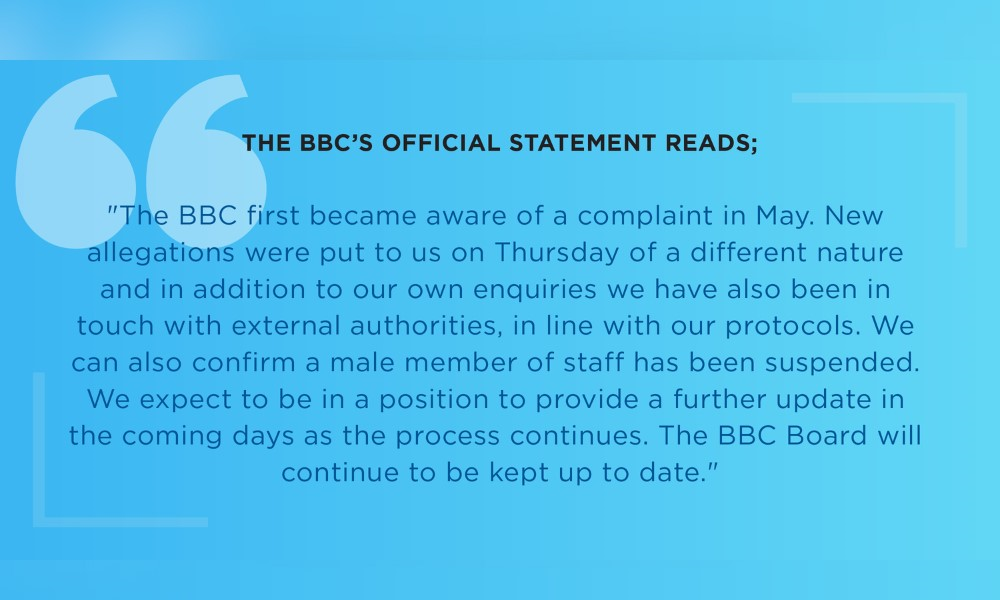

Earlier this week, the BBC made headlines once again when long-time presenter Huw Edwards was embroiled in a scandal involving allegations around paying a teen for explicit pictures. The case has taken twist after turn – with the police now announcing that there’s no evidence of a crime having been committed.

However, Edwards has removed himself from social media, with his wife releasing a statement saying that he’s “suffering from serious mental health issues” and is “receiving inpatient hospital care, where he will stay for the foreseeable future.”

With conflicting information coming from all sides, for HR leaders it’s a lesson on how to navigate allegations of misconduct, duty of care and, most importantly, the mental wellbeing of your people.

When an employee, even a high-ranking one, has allegations made against them, HR need to act quickly but decisively.

Speaking previously to HRD, employment lawyer Mike MacLellan, partner at CCPartners, says that when you’re investigating your superstar employees, the process shouldn’t be any different.

“As an employer, you have to make sure that you're aware of the circumstances of every particular investigation - but you don't get to not investigate a complaint just because the potential respondent is a superstar employee, or has some kind of position of importance or authority,” he explains.

“If the employer decides to conduct the investigation, you really need to consider if there’s an external individual who might be more suited – especially where conflict of interest is a concern. There’s plenty of independent and impartial investigators who can help here.”

When allegations arise, it’s essential that employees go to HR first. In this case, some journalists have spoken out about how the investigation was handled – with one saying that individuals should have gone to HR instead of focusing on breaking news coverage.

Speaking on a podcast, presenter Emily Maitlis was critical of the BBC’s coverage of the incident.

“There is something a bit distasteful,” she said. “If you know this stuff about a colleague, why isn’t your first duty to then go to HR or a senior manager? Or to say, ‘I think this is going on’ - rather than to turn it into a news story.”

According to The Metro, Maitlis went on to say: ‘Whilst you never want journalists to stop doing their job, you are in a really weird place if the way that you raise your concern about a fellow presenter or colleague is not through a HR process, not through a complaints process, but by breaking a story about them because they’re famous.”

It’s adhering to the proper processes that ensures all investigations are above board and all complaints are dealt with properly. What organizations need to avoid is people taking on the investigations themselves, which can lead to gossip and bad practice – all of which compromise an employer’s duty of care.

Cases like this one are always a doubled-edged sword for HR leaders. On the one hand, HR needs to act quickly and decisively in stamping out allegations of misconduct. On the other, especially when your organization is well-known, practitioners have to manage the inevitable PR disaster.

In a previous interview with HRD, TJ Schmaltz, SVP HR at Westminster Savings, says that a reliance on your people – and your culture – will help you through any troubling times ahead.

“PR nightmares really are disasters,” he told HRD. “The biggest issue is to ensure you’re getting your employees to help you manage the problem early.

“Your employees are what will make or break your success during this difficult time. Employees are on the frontline when it comes to customer concern and media outreach. And even though you might brief staff not to speak to the press, there’s still a possibility that they will – so it’s essential they know what to say, especially to your customers.”