'Comparing compensation is one of the most challenging things in doing a Pay Equity Plan, particularly for an employer that has many different collective agreements or ways of compensating employees'

A recent decision by Canada’s Pay Equity Commissioner Lori Straznicky sends a clear message to employers: when it comes to pay equity, one plan – usually – does fit all. The ruling emphasized that regardless of complicated or significantly differing payment structures, creating multiple pay equity plans within one organization defeats the intent of the Act.

For Canadian HR professionals navigating this legislation, the takeaway is simple but significant: employers should be ready to roll out a single, comprehensive pay equity plan that accounts for all job classes and types of compensation.

The requirement, aimed at addressing gender-based systemic pay disparities, sets a high standard for inclusivity and transparency.

The Federal Pay Equity Act is built on a clear principle: a single pay equity plan should cover all roles in an organization, allowing for consistent and equitable comparisons across job categories.

As Isabelle Roy-Nunn, a labour lawyer with Goldblatt Partners in Ottawa, explains, “The idea behind the federal Pay Equity Act is really to look at all of the jobs in one establishment, one employer, and put all of these jobs on the same comparison scale.”

This is why, she says, attempts to separate pay equity plans are usually rejected by Straznicky—companies are expected to include all employees under one equitable umbrella.

In Lower Lakes Towing Ltd. (Re), 2024 PEC 20, an employer applied for two separate pay equity plans, citing different pay structures for vessel-based and shore-based employees. However, the Commissioner dismissed this approach, stating: “Establishing multiple plans is an exception to the rule under the Act that an employer must create a single pay equity plan for its entire workforce”

One of the more challenging aspects of preparing a pay equity plan is determining exactly what “compensation” means in practice; the Act requires employers to account for more than just salary, with pensions, health benefits, and leave provisions all included in the equation.

Under the Act employers are required to compare different types of compensation across diverse job roles, essentially by reducing them to dollars per hour. For HR professionals, this means the focus should be on fairly comparing the total value of various compensation packages—no matter how different they might be.

The Lower Lakes Towing decision affirms this, Roy-Nunn says.

“Comparing compensation is one of the most challenging things in doing a Pay Equity Plan, particularly when you're looking at an employer that has many different collective agreements or many different ways of compensating their employees,” says Roy-Nunn.

“In this decision, [Straznicky] says, ‘Well, that's really not a reason, because we know this, and we've given you tools to help you figure this out, and the Act sort of predicted that this would be an issue and you're just going to have to do the work, ultimately.’”

For unionized workplaces, a collaborative pay equity planning process is essential, says Roy-Nunn.

The Act mandates that union representatives be actively involved in developing pay equity plans, a requirement that has the potential to lead to misunderstandings; as Roy-Nunn explains, some employers mistakenly think they can simply assign someone from the union to participate; “employers believe that they can simply select somebody and say, ‘Hey, you now represent your union on the Pay Equity Committee.’”

These misunderstandings can escalate when employers impose restrictive non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) on union representatives, sometimes leading them to believe they can’t consult with others in the union.

Roy-Nunn highlights that, in some cases, these representatives may not fully understand their role: “They impose very serious non-disclosure agreements on them…that make them believe that they can’t speak to anyone other than committee members about it.”

When employers sidestep collaboration or transparency, disputes can arise, leading to delays and potential complaints, she says.

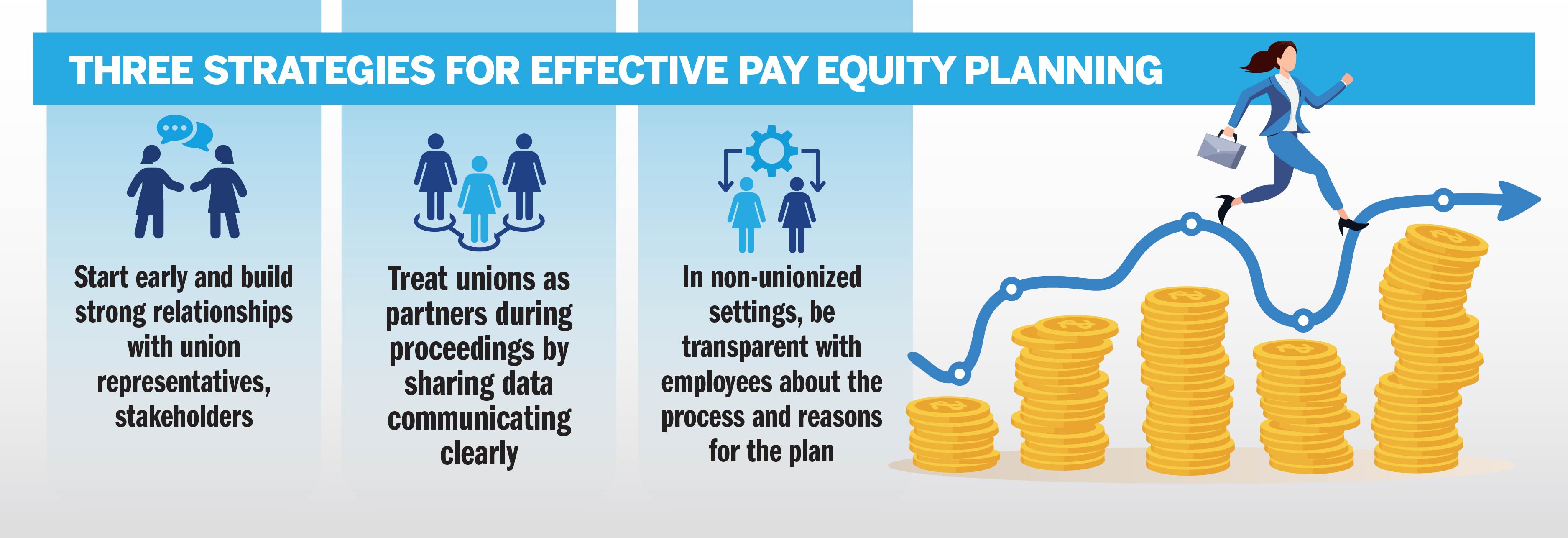

For employers looking to keep the pay equity planning process smooth and compliant, Roy-Nunn advises starting early and building strong relationships with union representatives. She emphasizes, “Work with the unions to get this done. Don’t make it an oppositional process. It really is meant to be a consensus-based process.”

Collaboration and transparency are not only helpful but crucial to avoiding unnecessary setbacks. HR professionals can play a pivotal role by treating unions as partners, sharing data openly, and fostering clear communication.

In non-unionized settings, employers should be transparent with employees about the process and clearly communicate the components of the pay equity plan, and with interest charges on delays starting from September 2024, Roy-Nunn stresses, beginning this work sooner rather than later can help avoid penalties and rushed planning.

Finally, she advises employers in unionized and non-unionized settings keep the spirit of the Act in mind when preparing plans and negotiating on committees.

“The relationship the Act creates here is different than any other relationship that exists in labour relations, right?” Roy-Nunn says.

“Ultimately, the goal of this exercise is to reach pay equity, and that is the one thing that the parties should keep in mind as their views diverge along the way. You're all trying to make sure that pay equity is achieved in this workplace.”