'People don't want to go back there; they want to work – and if given the chance, they’ll work hard and loyally'

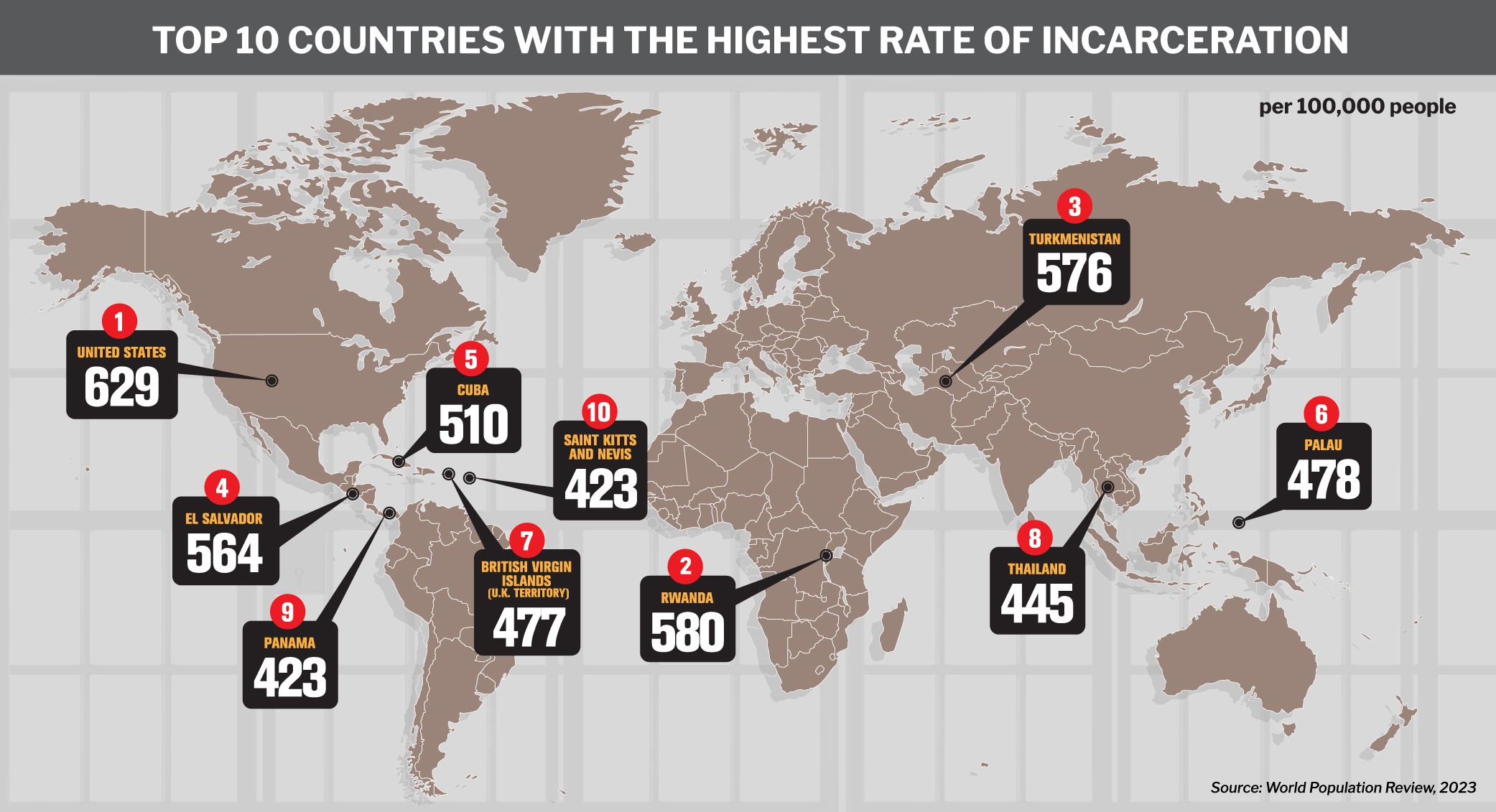

It’s estimated that there are currently 11.5 million people incarcerated across the world – with the United States leading the charge, with over two million people in prison.

Despite the size of this group, trying to find a job after having spent time incarcerated is an uphill battle for many. LeRon Barton, race and equity expert, likens it to a Nathaniel Hawthorne novel.

“It’s like they’ve been branded with the Scarlet Letter,” he tells HRD. “There’s this misconception that these people are forever a criminal, that they deserve to be punished even after they’ve served their time. And it’s just not fair or true.”

Candidates looking for work after being incarcerated are up against all kinds of bias, discrimination and even abuse. According to data from Zippia, only 25%-40% of formerly incarcerated people (FIP) have a job after a year of being released – with the average annual income for prisoners on release sitting at $19,610. What’s more, up to 89% of formerly incarcerated people who are rearrested are unemployed at the time.

As Barton tells HRD, this problem is systemic. It’s a mistrust of formerly incarcerated people stemming from an overall sense of societal prejudice - as well as a generalization and an inability to see the spectrum of crimes that can lead to prison time.

“It’s about understanding the different types of felonies people have committed,” he tells HRD. “There’s the people in there that deserve to be locked up – the murderers, the rapists, the pedophiles.

“On the other hand, you have this group that commit petty crimes out of necessity or an error of judgement. That group deserves our help - they deserve to have the opportunity to find employment afterwards.”

For Phil Martin, he knows this struggle first-hand. A successful businessman, in 2010 he had a number of employees on tag with convictions. He also spoke at a parole hearing in 2005 to help secure the release of a life sentence prisoner, getting him work and adding that since then, he’s never reoffended.

What Martin didn’t expect was that sometime later, during the infamous Credit Crunch disaster, he’d be jailed for fraud and fraudulent trading.

“I didn’t want to dismiss my staff,” he tells HRD. “So I kept trading. I ended up doing four years in prison – two in closed conditions and two in open. When I arrived in the open prison, the National Careers Service had just had its funding cut - the careers department in the resettlement prison was literally closing within a matter of days.”

Seizing the opportunity to help, and pulling on his business acumen, Martin set up his own internal careers department – helping people with their CVs, their disclosure letters and giving overall advice on how and where to land a role.

“It was hugely successful,” he tells HRD. “We helped hundreds of people into employment from inside the prison itself.”

Seeing the need to help formerly incarcerated people find much-needed jobs, upon his release Martin threw himself into his new passion and launched Ex-Seed – a recruitment consultancy to help former prisoners and people in the community with criminal records.

“People leaving prison need that extra help and support,” he tells HRD. “This idea that prison is a holiday camp or a free ride – it’s complete nonsense. The majority of people in prison don't want to go back there, they don't want to reoffend. They want to work - and if they're given an opportunity, then they will work really hard and loyally for the company that employs them.”

And it’s these outdated misconceptions that are driving bias. The unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people sits at 27% - staggering considering the global average is just 5.8%. And while a 2022 Working Chance report found that 45% of employers would consider hiring someone with a criminal history, 30% of hiring managers admit they’d instantly reject a candidate if they found that out – even if it went directly against company policy.

Why? It stems from a lack of trust and inherent misunderstanding.

“There’s this generalization that formerly incarcerated people are untrustworthy in the workplace,” says Barton. “Let me tell you, nothing could be further from the truth. If you hire someone who’s been in jail, they will be the most loyal, most hardworking and dependable employee you have.

“They’ll be the first one there in the morning and the last one leaving at night – because they understand the chance they’ve been given. They’re incredibly grateful, they’re productive – they have an extraordinary work ethic.”

This bias seems to be dissipating somewhat, however there are still a slew of issues facing candidates who have been in jail. Martin tells HRD that, actually, a lot of employers would be fine hiring someone who’s been in prison – the main concern stems from reputational or brand damage.

“Say, for example, a candidate goes for an interview with a huge tech giant – in their probation period they will face an adverse media check. That means a third party company searching on Google and Bing to find any ‘bad press’. Say, even if that person never had a criminal record, but they've been involved in some form of embarrassing publicity, that will be enough for them to fail the probation period.

“Imagine adding a criminal record into that. Whatever conviction, large or small, whether they served time in prison or not – that media check will drag it all up. And that bad press has a far greater impact than the conviction itself.”

Martin is involved in a project called Internet Erasure – a company that’s already helped over 500 people so far. Its mission revolves around the “right to be forgotten” – essentially, removing searches from Google so the content is no longer online.

“There’s various levels to it,” he says. “So if someone has an historic conviction, and it’s minor, we campaign to have that taken down. And that’s a massive barrier removed for that candidate.”

For companies hiring swathes of candidates, compliance and “box ticking” is a way of simplifying the process – using it to weed out people without having really given them a chance. Barton agrees that employers need to remove the box ticking approach to hiring and start looking at what really matters – the skills.

“Let’s get rid of that ‘Have you been convicted?’ question on job applications,” says Barton. “Employers should be looking at whether the candidate has the abilities to do the job. Do they have the education, do they have the ambition and drive? Never mind that they made a mistake in the past – let’s leave it in the past.

“It’s almost like it's an acceptable form of modern-day bigotry – like a certain group of people are set higher and the others are ‘untouchables.’ Having been in prison doesn’t mean you’re a bad person. Yes, there are certain people in jail, serial killers and child molesters, that need to be there. But people busted for selling a small amount of drugs, people that commit crimes out of sheer desperation, they deserve a career and a chance.

“We live in a land of second chances, after all – let’s start acting like it.”