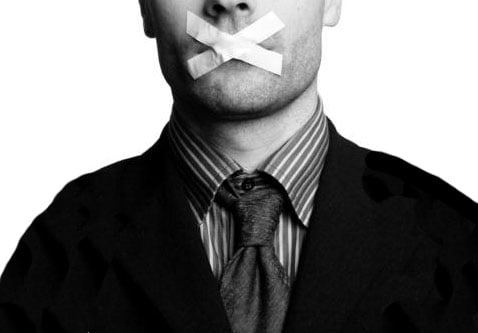

One new survey shows productivity takes a tumble when talk turns to politics – but can HR really ban political chat?

Almost everybody has something to say about the current state of global politics but the topic can cause tension in the workplace and employees can be left feeling polarized – so what should HR do?

“I do think we need to create some kind of policy which talks about behaviour and how we communicate,” says Dr. Steve Albrecht, an expert in high-risk HR issues.

According to Albrecht, employers should have a policy which says something along the lines of; “We work in the same place. Despite differences in a number of issues, we act as one team and one organization, so we need to be respectful and respected by our peers.”

Albrecht’s advice comes on the back of a new study – released earlier this week by research firm Clutch – which asked 1,000 full-time employees about their experience of political talk in the workplace.

Worryingly, 12 per cent of respondents said they had felt uncomfortable in the past week alone due to political expression at work. While it may seem a small figure at first glance, the study’s authors warned that it could have as serious impact on company culture.

If more than one out of ten employees are made to feel like they do not belong, or their opinions are not being respected, a serious issue can arise for leaders attempting to create an honest, open, comfortable environment, they warned.

California-based Albrecht agreed the issue posed a serious problem and said it was being compounded due to the 24-hour news cycle and ease at which anyone can access information.

“The issue which we're facing at the moment, and which wasn't one in the past, is that everyone is dialled-in and connected all the time,” he said. “People have become obsessed with this type of exposure to information at work, and are becoming distracted by political arguments.”

The same Clutch survey found that 31 per cent of employees felt their company’s productivity had been adversely impacted as a result of political talk and half of those who had felt either distracted or uncomfortable wished their company would implement an official policy.

According to the same study, just 45 per cent of companies have guidelines in place at present.

“Boundaries are the biggest benefit of developing a policy,” says Albrecht. “They can be used for discipline, if this is needed, or at least in coaching. If something hurts people's feelings, and interferes with a group's ability to do the job, we should regulate it.”

So how do HR professionals create a practical policy which puts appropriate boundaries in place without stifling employee’s free speech? Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, say the study’s authors.

Policies regarding political expression range from informal, conversational guidelines that are implemented through quick announcements at company meetings, to more formalized, structured policies that are established in an employee handbook, they explain.

While strict policies may include monitoring employee social media accounts or limiting an employee’s ability to publically engage with politics in campaigns, protests, or rallies, informal guidelines will focus instead on creating a culture of respect and consideration. It’s this more relaxed approach that Albrecht claims is usually more effective.

“A policy’s function is not to regulate free speech, but to make sure that people can do their work, and that the conversations they have don't hurt the business, or make others want to quit, transfer or give someone the silent treatment,” he says.