And where are all the workers?

Despite the Federal Reserve's aggressive policy of raising borrowing costs to combat the highest inflation since the 1980s, job growth in the United States remains strong.

Last February employers added another 311,000 new jobs, and wage inflation continued to increase – adding another 0.2% during the month.

Typically, interest rate hikes would cool the labor market, leading to higher unemployment rates.

However, despite the Fed’s recent flurry of interest rate hikes, current economic conditions suggest that this is not the case in 2023.

According to economists, the reason for this is classic supply and demand. The Fed's policy is focused on reducing consumer demand for goods and services by raising borrowing costs, which, in turn, reduces demand for workers. However, the Fed has limited control over the supply side of the equation, which refers to the number of available workers in the labor market – and this is where the current problem lies.

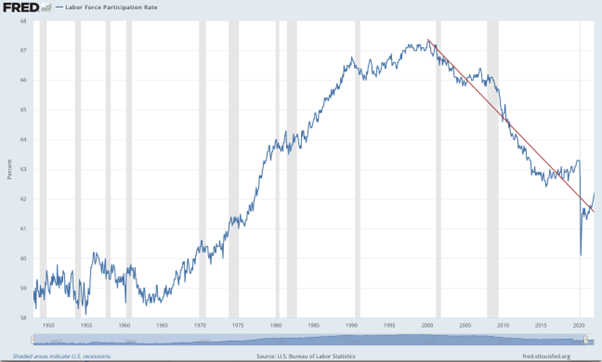

The participation rate, which measures the number of available workers in the labor market, plummeted at the beginning of the pandemic and has yet to fully recover to pre-COVID-19 levels. This is particularly true for men, who are participating in the labor market at a rate of 68%, which is 1.1 percentage points below February 2020 levels. This is equivalent to about 1.5 million men who are no longer part of the workforce. Current rates are as low as they were in the mid to late 1970s

This relatively low participation rate in the labor market is the primary reason why the job market is currently tight, which also explains why the Fed's interest rate hikes are not having much of an effect, but why is the participation rate so low?

The labor market experienced significant upheavals due to the pandemic. Initially, lockdowns led to a surge in unemployment rates, which was later followed by trillions of dollars in government aid aimed at supporting the economy. These events have resulted in structural changes that continue to affect the labor market today.

New research indicates that the lower participation rate in the labor market may also be partly attributed to younger workers joining the gig economy. This trend is not fully reflected in the government's job and participation figures.

The noticeable hump shape of the graph above rises from the long term 59-60% norm in the early 60s as women started to enter the workforce in larger numbers. Figures continue to rise until the 1990s, and then plateaus at around 67% before starting to decrease as the baby boomer generation starts to hit 62 and can claim benefits.

The biggest dip in the Labor Force Participation Rate occurred, unsurprisingly, alongside the Covid-19 pandemic when it slumped from 63.4% in Feb 2020 to 60.2% in April of the same year.

Overall, while the current job growth in the United States is positive news, policymakers will need to address the supply-side challenges in the labor market to ensure long-term economic stability.