The implications and controversies of NDAs - and how they’re reshaping HR policies and practice

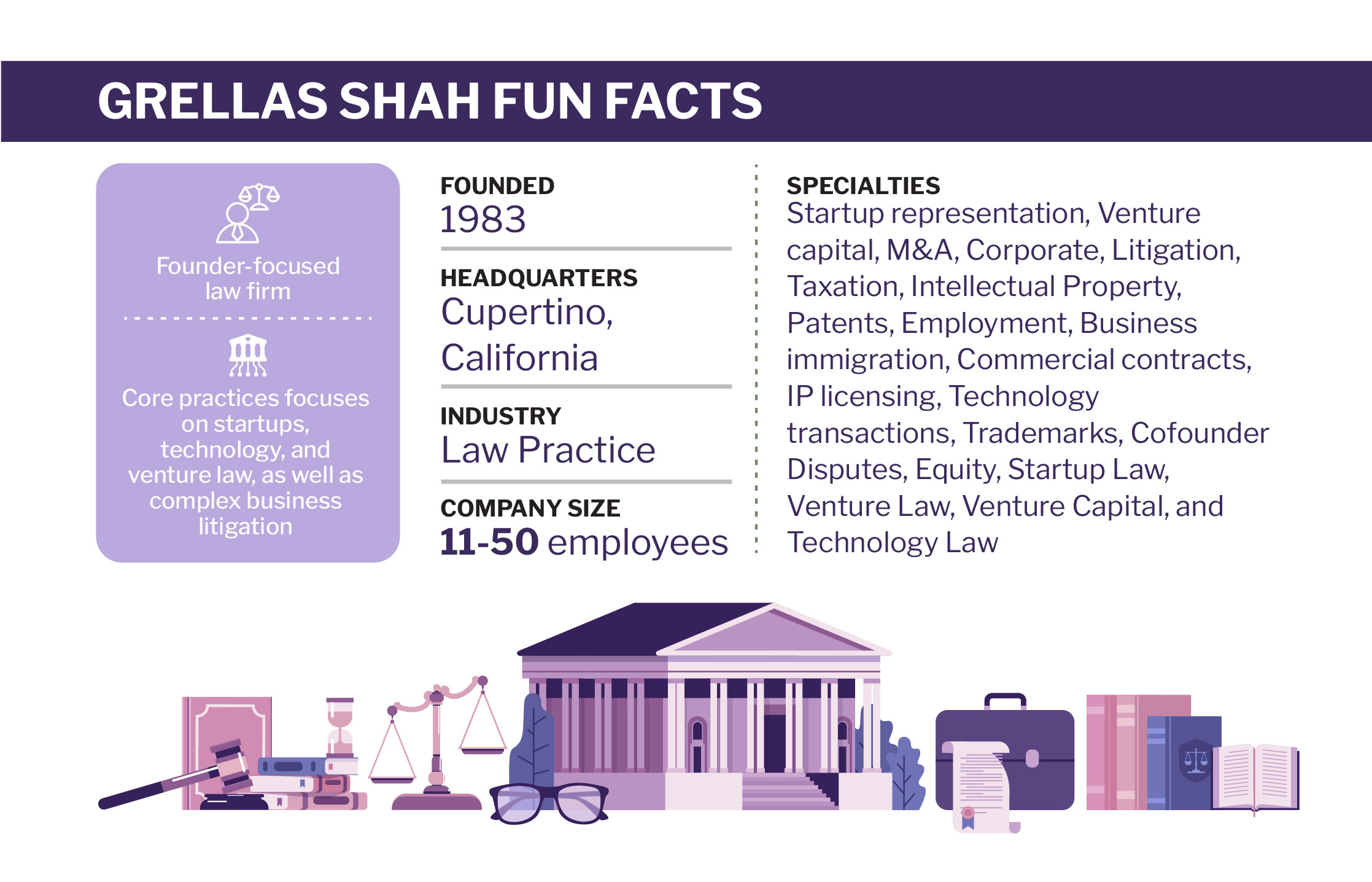

In the nuanced world of business, contractual agreements play a pivotal role – especially non-disclosure agreements (NDA). Often seen as complex and contentious, these documents are frequently misunderstood. David Siegel, Partner at Grellas Shah LLP, breaks down these integral policies, providing much-needed clarity for employers and HR leaders.

"I want to begin by underscoring that employees are often asked to sign what we refer to as 'restrictive covenants' at the beginning and end of their employment," Siegel tells HRD.

"Examples of these covenants are non-disclosure agreements and non-disparagement clauses. The latter is especially important, as it serves as a non-disparagement clause sample that can be adapted to the needs of the company.

"Confidentiality and non-disparagement clauses, or non-disclosures, are about the preservation of company specifics, such financials or technology. You're brought onboard, learn about the company, but cannot disclose that information - a fairly non-controversial agreement."

Learn the difference between a confidentiality agreement vs an NDA when it comes to protecting sensitive information here.

While non-competes may be enforceable in most states, courts scrutinize them meticulously. So what happens when an employee is terminated?

"That largely depends on where you are," Siegel tells HRD pointing out California's stringent laws against post-termination non-competes.

"Other places, like New York for example, are on the cusp of implementing similar legislation. Meanwhile, the Federal Trade Commission is considering making many non-competes unenforceable."

Siegel also brings attention to non-solicitation and non-disparagement provisions, adding that non-solicitation provisions, which may restrict you from soliciting employees or clients from your previous employer for a period, are similar to non-competes and must be time-limited.

“On the other hand, non-disparagement clauses, unlike non-competes and non-solicits, are almost always of infinite duration,” he adds. “They could apply to a wide range of individuals related to the company, such as officers, directors, employees, shareholders, and even customers and suppliers. This makes non-disparagement clause severance agreements particularly tricky to navigate."

In some cases, these non-disparagement clauses might even be deemed illegal.

"Non-disparagement provisions go a step further than defamation laws,” says Seigel. “They essentially state, 'You can't say bad things about me', irrespective of the truth of these statements. This raises questions about the legality of such clauses, leading some to label the non-disparagement clause illegal in certain contexts."

People don't really think about it, but non-disparagement clauses are almost never subject to subject matter limits, he says.

“Essentially, you're agreeing not to say anything negative about a broad range of people, which could trip you up years down the line. They aren't novel, but recent years have seen them becoming more prevalent, more expansive, and notably more controversial. The question of ‘How long does a non-disparagement clause last?’ is not often addressed directly in these clauses, leading to much confusion and potential legal disputes."

Siegel highlights the impact of movements like "Me Too," which sparked legal reforms preventing companies from silencing victims of sexual harassment.

"You can't be stopped from speaking out about such incidents in the workplace," he says.

Not only has this affected California, but it’s also influenced nationwide approaches to allegations of any law breaking in the workplace.

"The idea is not about truth, but about reasonable belief that there's been wrongdoing,” says Siegel.

Secondly, Siegel points to the landmark decision by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in the McLaren Macomb case.

"The NLRB looked at a broad, non-disparagement provision and struck it down, stating that such terms at the outset of employment violate the National Labor Relations Act,” he tells HRD.

The decision critiqued the rationale for having indefinite non-disparagement terms and questioned the legitimate business interests that these provisions served. To maintain a non-disparagement clause's enforceability, Siegel recommends that it should be time-bound and relate specifically to the work performed within the company.

"A non-disparagement term should be enforceable for a time-limited period and should pertain to matters associated with the work done in the company. This is one of the alternatives to non-disparagement clauses that employers can consider," suggests Siegel.

The changing landscape is a reminder to re-examine your company's non-disparagement and confidentiality provisions. These clauses must be tailored carefully to withstand legal scrutiny, strike a fair balance, and reflect a genuine business interest.

Additionally, staying abreast of landmark rulings like McLaren Macomb will ensure you're always in tune with the latest developments and best practices in the legal landscape of business agreements If you're navigating the complex arena of non-disparagement clauses, Siegel’s advice is to pause and critically assess the documents you're issuing.

"Take a step back, look at what you're asking people to sign and try to understand the pure business interest in this non-disparagement clause," he says. These provisions should be underpinned by a clear, legitimate business interest. It's not just about avoiding friction in negotiations but also dodging future litigation.”