Chief counsel of NLRB clarifies legalities, suggests alternate solutions for employers

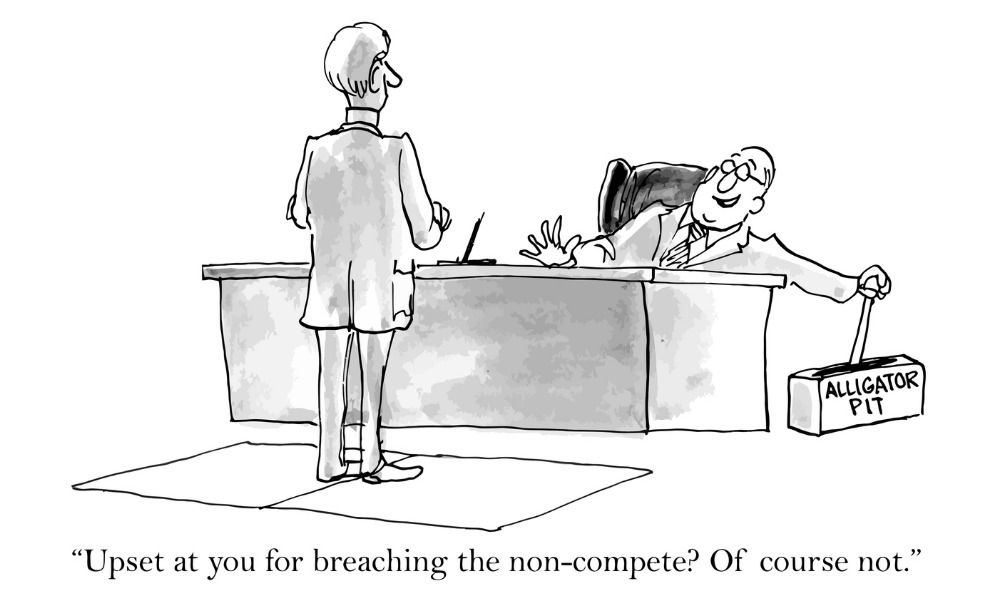

Requiring workers to sign agreements not to join competing companies is against the law, in most cases, according to a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) official.

“The proffer, maintenance and enforcement of a non-compete provision that reasonably tends to chill employees from engaging in Section 7 activity… violate Section 8(a)(1),” said Jennifer Abruzzo, NLRB chief counsel, in a memo to all regional directors, officers-in-charge and resident officers.

That is unless “the provision is narrowly tailored to special circumstances justifying the infringement on employee rights,” said Abruzzo.

In January, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) proposed a new rule that would ban employers from imposing non-compete clauses on their employees.

In March, lawyers voiced their concern over the proposal, with one saying it would have a “disastrous effect” on small businesses.

Noncompete agreements create a workplace environment in which employees are hesitant to raise safety concerns for fear of retaliation, said Abruzzo.

She said that: “they chill employees” from:

Abruzzo said that not all non-compete agreements necessarily violate the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA).

“Some non-compete agreements may not violate the Act because employees could not reasonably construe the agreements to prohibit their acceptance of employment relationships subject to the Act’s protection, for example, provisions that clearly restrict only individuals’ managerial or ownership interests in a competing business, or true independent-contractor relationships,” she said.

“Moreover, there may be circumstances in which a narrowly tailored non-compete agreement’s infringement on employee rights is justified by special circumstances.”

However, an employer’s desire to avoid competition from a former employee will not fall under special circumstances defense, Abruzzo said in the memo.

Also, business interests in retaining employees or protecting special investments in training employees are “unlikely to ever justify an overbroad non-compete provision because U.S. law generally protects employee mobility,” she said.

Abruzzo said that employers may protect training investments by less restrictive means, for example, by offering a longevity bonus. They can also protect proprietary or trade secret information by narrowly tailored workplace agreements that protect those interests, she said.

“In appropriate circumstances, Regions should seek make-whole relief for employees who, because of their employer’s unlawful maintenance of an overbroad non-compete provision, can demonstrate that they lost opportunities for other employment, even absent additional conduct by the employer to enforce the provision,” said Abruzzo.

“In this regard, Regions should seek evidence of the impact of overbroad non-compete agreements on employees and, where applicable, present at trial evidence of any adverse consequences, including specific employment opportunities employees lost because of the agreements.”

The power of non-compete clauses may be waning due employers’ struggling to fill job openings, according to one expert.